[First posted august 20, 2014, reposted September 17, 2015; part of a series of post featuring this MUST READ/MUST OWN book.

This chapter best explains in a way it has never been explained and understood before, that chosenness was actually not unique to Israel. Read on to find out more. We will feature only two chapters from this book, enough to get you interested in adding a copy to your library. It should be available, hard copy or ebook, on amazon.com or Ebay. If you cannot find a copy for yourself, email us and we will feature more chapters of this book. Images, editing and reformatting added.—Admin1]

——————————-

The Ancient Near Eastern Context

Ancient Near East is a slippery term because it overlaps with other terms such as Middle East, Fertile Crescent, and Mesopotamia. The area of the ancient Near East corresponds roughly with that of today’s eastern Mediterranean, from Greece in the west to Iran in the east, and Turkey in the north to Arabia and Egypt in the south. This area includes today’s countries of Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, Egypt, Jordan, Arabia, and Iraq. The time period of the ancient Near East ranges from as early as we have record until the cultural penetration of Greece and then Rome in the third century BCE. All the monotheistic religions find their roots in the cultures, languages and religious ideas of the ancient Near East.

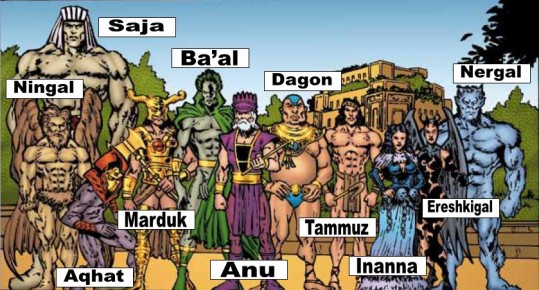

In this ancient human environment, the world and nature were understood to function under the powers of deities. Some of those deities had special jurisdiction over parts of nature, such as the weather, the waters, or the fertility of crops and herds. Others had special jurisdiction over groups of people organized around kinship. In the ancient Near East, national groups were organized through large kinship networks. Members of tribal nations belonged to nuclear families which functioned as parts of larger extended family clans, which in turn were parts of much larger extended kinship groups that we call tribes.

As in the case of biblical Israel, related tribes made up a “nation” or a people, and in the ancient Near East, every national unit seems to have had its own national goddess or god.

There were other divine powers besides the national god, but each nation had a unique relationship with its “own” god. If you were a Moabite, for example your national god was Kemosh. Kemosh protected you and your kin. He would also make sure your crops and your flocks were fertile, and protect you and your family and tribe from attack by foreigners. In return, you make offerings to him and demonstrated your loyalty and that of your family to him. The gods of other nations would normally take no interest in you, nor you in them. Born a Moabite, you were born into a community that worshipped its Moabite god, Kemosh. You could no easier change gods or religions than you could change your family history. Nevertheless, if you were in a foreign land, you would most likely make an offering to the local god as a form of respect and a means of gaining needed temporary protection in the area under the god’s jurisdiction. Because there were many deities that powered the world, you might wish to hedge your bets and make sure that offerings were made to certain foreign gods as well as your own national deity even when not traveling.

One particular feature of religious life in the ancient Near East is that all believers were “chosen” by their national gods. While believing in other divine powers that inhabited sacred areas or protected other peoples, every nation had its own exclusive relationship with its own national god.

The god of the Hebrew Bible is sometimes called the “God of Israel” (Gen. 33:20), but it also had a personal name, like all other gods. As mentioned in Chapter 1, that name conveyed a meaning similar to “being” or “existence.” Although the name was no doubt pronounced at one time, its articulation was eventually forbidden. The reason for this prohibition is probably associated with issues of relationship and power. If you know someone’s name, you have a certain advantage, even power, over them, particularly if they do not know yours . . . . In some traditional societies, people change the name of sick children in order to confuse the angel of death or demon who might take the child. Without knowing the child’s name, the demon doesn’t have the power to take him or her.

In polytheistic systems, humans try to influence the gods through persuasion or manipulation—sometimes even through magic. In the polytheism practiced in the ancient Near East, people knew the names of their gods and used the names for this persuasion and manipulation. But in monotheism there is only one great Creator-God, the one all-powerful God of all. Humans could not possibly have the power or strength to manipulate the awesome God of all creation. It therefore became strange to refer to the One Great God by a personal name.

Biblical scholars agree that the Israelites once related to their God of Israel like other tribal nations related to their own national gods. Each god had a name and each was limited in power. But the Israelites made the transition from polytheism to monotheism, and the God of Israel transformed in the eyes of the Israelites to become the God of the entire universe. Although God did not change, the human conception of God changed during this transition period. So the once-named God became known as “the Lord” or simply “God”—the source of being, the all. After that transition occurred, it seemed impossible for humans to pronounce God’s name.

Keep in mind also that in the old polytheistic religions knowing and uttering a god’s name was thought to release some of its power. With that notion in the background, uttering the name of the One Great God might endanger the entire community by releasing some of God’s unlimited power. That notion seemed to linger among the ancient Israelites, so it evolved into the belief that you would have to be extremely powerful and protected in order to mention God’s name without being consumed by the very force that might be released.

While the Jerusalem Temple was still standing, ancient Israel had a ritual ceremony in which the name of God was actually uttered, but this was done in a carefully controlled manner. In fact, according to the second-century book of Jewish tradition called the Mishnah (Yoma 6:2), it actually became an annual ritual requirement that took place on the most sacred day in the calendar, Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement). This most sacred utterance of the divine name could be pronounced only on the holiest day of the year. It had to be pronounced in the most sacred location on earth—the inner sanctum of the Jerusalem Temple, known as the Kodesh Kodashim (the Holy of Holies). And it could be uttered only by the most highly consecrated individual on earth—the high priest, who had to endure a period of careful physical and spiritual preparation in order to attain the required state of absolute ritual purity. According to rabbinic tradition, a rope was tied around the high priest’s ankle in the event that he was not properly prepared, ritually and spiritually, for the uttering of the divine name. If he failed, he would be burned up within the Hoy of Holies and his body could only be retrieved by having it dragged out. In the event of such a catastrophe, a second high priest went through the same preparatory process in order to be prepared to utter the divine name in his place.

So the pronunciation of the name of the God of Israel became forbidden and eventually lost. But for centuries before the transition to monotheism, the ‘God of Israel” was exactly that—limited to the Israelites (see Exod. 5:1, for example).

As noted, the Moabites who lived next to Israelites, in the hill country to the east (today’s central Jordan), had their own national deity named Kemosh (Num. 21:29).

North of the Moabites were the Ammonites, whose national god was Milkom (1 Kings 11:6).

The Philistines, who lived on the plain to the west of ancient Israel between today’s Gaza and Tel Aviv, had Dagon as their god (1 Sam. 5), and further up the coast, the inhabitants of Tyre had a goddess named Ashtoret (2 Kings 23;13).

Each ethnic community had a unique relationship with its god. They were “chosen” for each other. The god protected its community, provided for it, and fought for it. In return, it was worshiped and offerings were made to it. In the ancient world, the normal tensions that arose between ethnic or national communities were often mirrored by tension between their gods. An oracle to King Esarhaddon, who ruled the Assyrian Empire from 680 to 669 BCE, demonstrates the protector role not only of the gods, but also of the goddesses. The god’s personal name was always given to identify the specific source of the power: “Esarhaddon, king of the lands, fear not! That wind which blows against you— I need only say a word and I can bring it to an end. Your enemies, like a young boar in the month of Simanu, will flee even at your approach. I am the breat Belet—I am the goddess Ishtar of Arbela, she who destroyed your enemies at your mere approach.” Wars between nations may have been fought by tribal soldiers, but victory or defeat was determined by national gods. Wars were won or lost according to the fighters’ ability to please their gods.

The God of Israel was assumed to have fought along with the Israelite people in their own wars. In the victory song intoned after the defeat of Pharaoh’s armies in the Red Sea, God is praised as ish milchamah (the warrior; literally, “Man of War,” Exod. 15:3). And when Israel is preparing to conquer the land of Canaan under God’s direction, they are reassured:

When you take the field against your enemies and see horses and chariots—forces larger than yours—have no fear of them for the Lord your God who brought you from the land of Egypt is with you….Do not be in fear or in panic or in dread of them, for it is the Lord your God who marches with you to do battle for you against your enemy, to bring you victory! (Deut. 20:1-4)

We must keep in mind that the Hebrew word that is translated as “Lord” is actually the four letters that make up the “personal name” of the God of Israel. “Lord your God” in this passage originally would be rendered by God’s personal name, followed by the description, “your God,” so the reassurance was given in the actual name of Israel’s own national deity.

The Hebrew Bible contains a number of stories that demonstrate the special relationship of a god with its people in time of war. One particular interesting example is a war between the Moabites and Israelites. This story is especially important because it is recorded both in the Bible, in 2 Kings 3, and in another ancient Near Eastern text, a stone monument called the Mesha Stele (for Moabite Stone). The Mesha Stele is an ancient basalt table written for the Moabite king Mesha in about 850 BCE; it was written in Moabite, a language so close to Hebrew that they can be understood as dialects of the same language. It records the same story found in 2 Kings, but from the Moabite perspective. The two sources tell us that the war actually happened, but provide two conflicting versions of the outcome. In the following two versions of the story, if you substitute an actual divine name for “the Lord” in the Bible version, or if you substitute “the Lord” for the name Kemosh in the Mesha version, you can see how similar the styles of the two versions are.

According to the Bible, the Moabites were weaker than the Israelite and had fallen under Israelite rule. As a result, they paid heavy taxes to Israel. But the king of Israel “did evil in the sight of the Lord,” for which the God of Israel allowed the Moabite king Mesha to rebel. In response, the Israelites assembled a coalition of three kings with their armies and set out to reconquer the Moabites. They expected to find water in a certain ravine to resupply their troops near the field of battle, but found the water source to be dry. This became a key issue in the battle that followed.

“Alas!” cried the king of Israel. “The Lord has brought these three kings together only to deliver them into the hands of Moab!” But when the Israelite leaders consulted a prophet of God to determine whether God would support them, the prophet went into an oracular trance and proclaimed, “Thus says the Lord: This ravine shall be full of pools. For thus said the Lord: You shall see no wind, you shall see no rain, and yet the ravine shall be filled with water; and you and your cattle and your pack animals shall drink. And this is but a slight thing in the sight of the Lord, for He will also deliver Moab into your hands” (2 Kings 3:10-18).

As the holy man prophesied, water began to flow and the Israelites were refreshed. The Moabites were then tricked into attacking the Israelite camp but were routed. The Israelites overpowered all the Moabite cities and pushed the remaining army into the walled city of Kir Hareshet. Things did not get any better for the Moabites there. They became trapped behind the walls of their own fortress when they failed in their attempt to send a column for help. Suddenly, after that sacrifice, the Israelites withdrew and the story ends.

It is not clear from the biblical text exactly what happened as a result of the sacrifice. The literal translation of the Hebrew is,

“So [King Mesha] took his firstborn son, who was to succeed him as king, and offered him up on the wall as a burnt offering. A great wrath came upon Israel, so they withdrew from him and returned to [their own] land” (2 Kings 3:27).

The Mesha Stele tells a different version of the story. According to this version written by King Mesha, the king of Israel “oppressed Moab for many days”:

for [the Moabite god] Kemosh was angry with his land ….But Kemosh restored it in my days … the king of Israel built [the city of] Atarot for himself, and I fought against the city and captured it. And I killed all the people of the city as a sacrifice for Kemosh and for Moab. And I brought back the fire-hearth of his uncle from there; and I brought it before the face of Kemosh in Qeriot … and Kemosh said to me, “Go, take [the city of] Nebo from Israel.” And I went in the night and fought against it from the daybreak until midday, and I took it and I killed the whole population … and from there I took the vessels of YHWH [the four-letter name of the Israelite god preserved in the stone tablet], and I presented them before the face of Kemosh. And the king of Israel had built [the city of] Yahaz, and he stayed there throughout his campaign against me; and Kemosh drove him away before my face.

Each version of this story has a particular point of view and tells the tale as a partisan advocate. There is clearly no interest or attempt to offer a neutral report, but it is clear that from the perspective of each side, it is the relationship with the national god that is key to winning wars.

The Bible often relates to the God of Israel from a parochial perspective, though as the notion of the God of Israel expanded to the notion of a single God of the entire world, the perspective changes. Some biblical texts depict a global perspective where, for example, the God of Israel destroys all the gods of the Egyptians: “I shall execute judgment, I the Lord, against all the gods of Egypt” (Exod. 12:12). In others, God uses the Assyrians or Babylonians as a tool to punish Israel when it is sinful, even to the extent of destroying the northern kingdom of Israel by the hand of Assyria (2 Kings 17). By the time God is understood in purely monotheistic terms, the gods of Babylonia or other competing nations no longer figure in the narrative. They have dropped out because they are no longer considered to exist.

Choosing Religion

Because Israel seems to have been the only community to make the transition from polytheism to monotheism in this period, it saw itself situated in a world of false gods. In such a religious environment where a person naturally remained loyal to his or her ethnic religion and national deity, Israel remained loyal to the “God of Israel,” whom they also saw as the God of the entire universe. Even (or perhaps especially) after the transition to monotheism, absolute loyalty to their God became critical. Disloyalty did not mean simply abandoning one god for another, for that was impossible. In their world, disloyalty meant continuing to hedge their bets as in the old polytheistic world, when the God of Israel was understood to be the one and only God of the universe. It meant making offerings to other powers in addition to worshipping the One Great God, the God of Israel.

We can imagine the enormity of difference between Israelite religion and the religious practices of all its neighbors if we think about all the various ethno-religious communities of the ancient Near East as practicing one overarching religion. The Moabites and the Ammonites and the Kenites and the Jebusites may have worshipped different gods, but they all followed the same assumptions about how those gods functioned and how religion worked. They were all practicing the same religion even if their worship was directed toward different deities. Israel was the only community that practiced according to a different religious concept.

It might appear odd that Israelites did not proselytize. Although the Bible records how the transition from polytheism to monotheism took time and was sometimes rocky (see, for example, all the polytheistic practices that were removed from Jerusalem by King Josiah in 2 Kings 23:4-15), the Israelites eventually became confident in their monotheism and deeply faithful to God. Yet, it seems they did not try to bring the “good news” to others steeped in the falsity of idolatry. This may seem strange from our perspective, but the truth of the matter is that mission was not really a possibility in those days. The religious environment of the ancient Near East was radically different from ours today, where religions openly compete with one another for members in a “free market” of religions. In the ancient world of ethnic religion, it was simply impossible to abandon your national god. In those days, the notion that you could believe or disbelieve in a religion was not a conceptual option. The world was perceived as functioning according to the divine powers that ran it, and there was no possibility to even conceive of something different.

In fact, the notion that you could scope out religious options and choose the one that made most sense was not a conceptual possibility in the Near East until the Greeks imported the notion through their interest in philosophy. It was the Greeks who developed philosophical schools, each of which offered a different way of making sense of the world. In the great Greek cities, you could attend various schools, learn their philosophies, and consider which to subscribe to. These were philosophies rather than religions, but it was simple enough for people to apply the notion of deciding which philosophical system made most sense to which religious system made most sense. This idea would not come to the land of Israel, however, until later. Before the Greeks brought Hellenism with them from within the borders of Hellas to the rest of the Near East, religious affiliation was a national affair.

The God of Israel had been understood by Israelites in the early period of their history to be a tribal god parallel to the tribal gods of neighboring peoples. Israel’s god was (hopefully) more powerful than other gods, as seems to be the sense of Exodus 15:16: “Lord, who is like You among the gods? Who is like You, majestic in holiness, worthy of awe and praise, worker of wonders?” (see also Exod. 12;12, Num. 33:4). But in the early period, the God of Israel functioned very much like the gods of the neighboring peoples, the “gods of the nations” (Ps. 96:5).

For some reason or reasons that remain matters of debate among theologians and historians of religion alike, religious ideas began to change among the Israelites. This seismic shift seems to have occurred during the period of the great classical prophets (roughly, the eighth to the sixth centuries BCE). The prophets insisted that the God of Israel was also the God of the entire universe. By the time of Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel, Israelite religion held firmly that the God of Israel was actually the only God: “I am the Lord, and there is none other; apart from Me there is no god” (Isa. 45:5).

The Emergence of Monotheism

Although it is perhaps surprising, Israel was not the only community to have arrived at the notion of monotheism, and it may not have been the first. Other monotheisms or proto-monotheisms such as that of the Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten, may have existed for a limited time, but they could not be sustained. Israel was the only community that sucessfully held on to this view in the ancient Near East. Because it was the lone monotheist community, it was constantly on the defensive in a world full of enticements to engage in worship of foreign gods (Num. 25:1-9; 2 Kings 23:4-15).

Once the God of Israel was known as the God of the universe, it became absolutely forbidden to engage in any activity that smacked of worshipping other gods. The old habit of hedging your bets by making offerings to other deities or powers in nature became strictly forbidden. Infidelity to the God of Israel is referred to in the Bible as straying after or worshipping other gods. (Exod. 20:2, 23;13; Deut. 5:6, 6:14, 11;16; Jer. 1L16, 7:6).

The transition to monotheism, however, was neither smooth nor total. Not everyone in the Israelite community was completely convinced that the old, premonotheistic Israelite religious practices of its earliest days were necessarily false or useless. The emergence of monotheism seems to have been a process, and the Bible itself is witness to movements to ban polytheism and countermovements to reestablish it. As noted above, a partial menu of the kinds of polytheistic practices that were available to ancient Israel can be seen in 2 Kings 23:4-15, a chapter that details King Josiah’s religious reforms. It mentions many of the old practices by listing all the popular and varied types of polytheistic worship that Josiah destroyed. He smashed the objects made for the Canaanite gods, Ba’al and Asherah and the Host of heaven, he suppressed the idolatrous priests throughout the land who made offerings to Ba’al and to the sun and moon and constellations. He tore down the cubicles of the male religious prostitutes that were situated within the Temple itself, and destroyed many altars and shrines, including the Tofeth in Gey Ben-Hinnom, where people sacrificed their children (they “passed their sons or daughters through fire”) to Molekh. He also destroyed the horses dedicated to the sun and burned the chariots of the sun, defiled shrines built for the goddess Ashtoret and the god Kemosh on the Mount of the Destroyer, and shattered the sacred pillars and posts.

According to the direction of current biblical scholarship, there were not merely foreign deities, the gods of the hated Canaanites. Some were actually gods traditionally worshiped by Israel. Biblical scholars such as Niels Peter Lemche have shown that Canaan refers more to a geographical area than a people, a land in which lived a variety of peoples that we know from biblical texts as Hittites, Girgashites, Emorites, Perizites, Hivites, and the like, often lumped together in the Bible (and Egyptian and Mesopotamian texts) as Canaanites. The Israelites lived there too.

Israel, it now appears, may have actually emerged as a distinct people out of the land called Canaan. According to many scholars of the Bible today (and putting it bluntly), Israelites were Canaanites, in the direction of an innovative religious idea that was becoming what we would later call monotheism. The Bible itself witnesses the bumpy road to the realization of that religious idea.

In the system articulated in the Hebrew Bible, responsibility to follow the revealed will of God found in the Torah is not a universal responsibility. It is directed specifically to Israel. It may seem strange to us that a religion espousing a concept of a universal God would appear to be unconcerned about the religious warfare and practices of those situated outside the receiving group, but recall that in the ancient Near East, religion was by definition distinctly ethnic. Each ethnic of national group had its own god or pantheon, and each national god had a unique relationship with its ethnic community.

The God of Israel may have become conceptualized as the one and universal God that created and now powers the heavens and the earth, but it was intimately known as the God of Israel, and it retained that distinctive relationship with its people. It would simply seem strange to Israelite and non-Israelite alike for this tribal organization of monotheists to try to convince other tribal organizations to abandon their gods for the God of Israel.

On the other hand, because of Israel’s unique position as the only monotheist community in the ancient Near East, intermarriage with peoples professing other religions was strictly forbidden. Such intermingling was liable to distract from the austere practices of monotheism among a small group living in a world of many peoples and nations, each associated with colorful, multiple deities and enticing worship rituals. The Moabites and Midianites seem to have been two of the biggest threats to Israel in this regard, and God warns Israel repeatedly not to follow the whims—or the women—of these neighboring peoples (Numbers 25).

Aside from the Israelites, however, intermarriage between peoples representing different religions may not have represented a significant theological problem in the polytheistic ancient Near East. If you traveled across national boundaries, you would pass from place to place but often find very similar gods. Those gods might have had different names, but they were easily recognizable by strangers because they occupied a similar or identical place on what you might call “the food chain of divinity.”

In virtually every ethno-religious system, for example, there was a god associated with fertility. That god may have different names in different places, but its job description was just about the same everywhere. Among the Israelites, on the other hand, one God was understood to control all aspects of nature and time, and Israel was permitted to worship only this only this one God, this “zealous god” (Exod. 20:4, 34:14; Deut. 4:24,5:8,15), who would tolerate no confusion or association with other deities. Intermarriage with people who worshiped their own national gods was always a threat to the unity and survival of this one small community. Even with those groups such as the Egyptians and Edomites, among whom the Israelites were permitted by biblical scripture to marry, intermarriage was allowed only after three generations of the foreigners had assimilated into the Israelite cultural and religious system (Deut. 23:8-9).

Israel was only one small ethno-religious people among the many peoples and religions of the ancient world. According to the sentiment expressed repeatedly in the Bible, Israelite religious leaders felt the stress of the theological insistence on monotheism in a world of multiple deities. Some neighboring religious systems, for example, had enticing ritual practices such as sacred prostitution, most likely human sympathetic acts such of public coitus in order to stimulate the gods to do the same and thus provide fertility to their people’s pastoral or agricultural economics (1 Kings 14:24; Hos. 4:12-19; Ezek 23:5-10). As Deuteronomy articulates the relationship,

[Many nations] … will draw your children away from the Lord to serve other gods …for you are a people holy to the Lord your God, and He has chosen you out of all peoples on earth to be his special possession.

It was not because you are more numerous than any other nation that the Lord cared for you and chose you, for you are the smallest of all nations; it was because the Lord loved you and stood by His oath to your forefathers, that He brought you out with His strong hand and redeemed you from the place of slavery, from the power of Pharaoh, king of Egypt.

Know then that the Lord your God is God; the steadfast God with those who lover Him and keep His commandments. He keeps covenant and faith for a thousand generations, but those who defy and reflect Him He repays with destruction ….Therefore, observe commandments the Instruction—the laws and the rules —with which I charge you today (Deut.7:6-11)

Chosenness in Historical Context

This citation from Deuteronomy is interesting for a number of reasons, but in order to arrive at a better sense of its meaning we need to consider the Hebrew language of the original. The text uses the verb bachar (choose) two times. The literal meaning of the Hebrew in verse 6 is:

“For you are a holy people to the Lord your God; the Lord God chose you [the you is emphasized in the Hebrew] for Him as a treasured people from all the peoples on the face of the earth.”

And in verse 9, the Hebrew literally reads,

“Know then that YHWH [the four consonants that make up the name of the God of Israel], your god, is The God, the [truly] trustworthy god, keeping the covenant of loyalty with those who love Him and those who keep His commandments to the thousandth generation.”

This foundational message has two parts.

- First, the God of Israel is the only true god.

- Second, that one true God chose Israel from all the peoples of the earth to be God’s own.

We have seen how this sense of unique relationship is natural in the ancient Near East. In the premonotheistic period, the tribal confederation known as Israel had a unique relationship with its own tribal god, known at one time by a personal name made up of four letters. It was, of course, logical for that tribal group to be the most beloved by its own tribal deity. When that god became conceived of as the One Great God of the universe, it was instinctive for the people to retain that feeling of special relationship between deity and tribe. In fact, being the lone community that revered the only real deity, the One Great God, probably enhanced the sense of special and unique relationship.

The term to choose is not the only reference to the special relationship between God and Israel indicated in the Hebrew Bible. The prophet Amos refers to the relationship with the Hebrew verb yada’, meaning “to know intimately”: “You alone have I known among all the families of the earth” (Amos 3:2). The language here is personal, with the word mishpachot (families) in place of the more common ‘amin (peoples).

“A people holy to the Lord …” in verse 6 of the Deuteronomy passage above (Deut. 7:6) is rendered in the Hebrew as ‘am qadosh …l’adonai. The root meaning of qadosh is “to separate, put aside or consider unique.”

In the religious context of the premonotheistic ancient Near East, Israel was probably no more unique in relation to its tribal God than any other ethno-religious unit was in relation to its own tribal deities. But when Israel had reached the point where it truly considered its god to be the One Great God of the universe, the relationship had indeed become unique. Given the reality of all other peoples recognizing multiple deities, the contextual environment required that Israel remain separate in order to survive under the heavy pressure toward religious assimilation.

In other words, the notion of chosenness originated simply as a natural part of old tribal religion. When Israel’s concept of divinity became one of universal monotheism, it was natural to continue to feel the special relationship. After all, the God of the universe is also known in the Bible as the “God of Israel.” That natural sense of chosenness also became a convenient and effective strategy to maintain a unique religious system despite the many temptations of polytheism.

All religionists of the period felt that they were “chosen” by their gods. But as we will observe in more detail below, every one of the Near Eastern tribal religions died out, leaving only the Israelites retaining the traditional sense of a “chosen” relationship with its once-tribal, now-universal God.

This does not mean that ancient Israelites necessarily felt smug about their chosenness, for even that they had consistent definition for it. The Hebrew Bible itself expresses disagreement over the meaning and responsibility associated with chosenness. Some references relate to the election of Israel as a unique privilege and benefit that God gave freely to Abraham and his progeny:

The LORD said to Abram, “Leave your own country, your kin, and your father’s house, and go to a country that I will show you. I shall make you into a great nation; I shall bless you and make your name so great that it will be used in blessings: those who bless you, I shall bless; those who curse you, I shall curse. All the peoples on earth will wish to be blessed as you are blessed.” (Gen. 12:1-3; cf. Exod. 19:1-6; Deut. 14:2).

Other biblical verses suggest that the Israelites earned their unique relationship through their merit. God said to Abraham after he proved willing to sacrifice his son in response to God’s command: This is the word of the Lord:

“By my own self I swear that because you have done this and have not withheld your son, your only son, I shall bless you abundantly and make your descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky or the grains of the sand on the seashore. Your descendants will possess the cities of their enemies. All the nations on earth will wish to be blessed as your descendants are blessed, because you have been obedient to me.” (Gen. 22:15-18; cf. Exod. 24:3-8).

Still other verses consider the status to be one requiring great responsibility and extraordinary behavior:

“You alone I have known [intimately] among all the families of the earth; that is why I shall punish you for al your wrongdoing” (Amos 3:2).

And other texts seem to render the chosenness of Israel as only a relative term, for God has chosen other peoples as well:

“When that day comes Israel will rank as a third with Egypt and Assyria and be a blessing in the world. This is the blessing the Lord of Hosts will give: ‘Blessed be Egypt My people, Assyria My handiwork, and Israel My possession'” (Isa. 19:24).

“Are not you Israelites like the Cushites to Me?’ Says the Lord. ‘Did I not bring Israel up from Egypt, and the Philistines from Caphtor, the Aramaeans from Kir?'” (Amos 9:7).

Because all ethnic religions in the ancient Near East considered themselves unique on account of their special association with their ethnic gods, the familiar human tendency toward ethnic elitism was naturally expressed through religious elitism as well. Conquering peoples often insisted that local populations include worship of the gods of the conquerors in local ritual.

The Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III (744-727 BCE), for example, had the following written about his conquest of Gaza: “As to Hanno of Gaza who had fled before my army and run away to Egypt [I conquered] the town of Gaza . . . his personal property, his images . . . [I placed (?) 9 the images of ) y [ . . . gods] and my royal image in his own palace . . . and declared (them) to be (thenceforward) the gods of their country.”

When the great Persian king Cyrus (557-529 BCE) conquered Babylon, he justified his conquest, in part, on account of the sin of the Babylonian king Nabonidus, who refused to worship the local Babylonian god, Marduk.

The lord of the gods (i.e. Marduk) became terribly angry and [he departed from] their region . . . . He scanned and looked (through) all the countries, searching for a righteous ruler willing to lead them (in the annual procession). (Then) he pronounced the name of Cyrus, king of Anshan, declared him to be the rule of the world . . . . I resettled upon the command of Marduk, the great lord, all the gods of Sumer and Akkad, whom Nabonidus has brought into Babylon to the anger of the lord of the gods, unharmed, in their (former) chapels, the places which make them happy. May all the gods whom I have resettled in their sacred cities ask daily (the gods) Bel and Nebo for a long life for me and may they recommend me.

Sometimes conquering peoples merged their own gods with local gods that had parallel “job descriptions.” Gods of the conquerors that were associated with certain attributes were sometimes fused with local gods having similar traits. When the Greeks conquered Egypt, for example, they simply merged their own system into the systems already in place in Egypt under the pharaohs.

The Greek kings then fancied themselves as pharaohs as well, with the result that the Egyptian god Osiris, for example, was merged with the Greek God Dionysis, and the Egyptian god Thoth with the Greek god Hermes. The result was the weakening of the local religions and assimilation to a system that was closer to the religion of the conquerors.

The Greeks brought not only their gods, but also their culture. The power and popularity of Hellenic culture influenced local cultures and “hellenized” them. This resulted in the emergence of what historians call “Hellenism,” a synthesis of pure Greek (Hellenic) culture with the local Near Eastern cultures. Many locals learned the Greek language and integrated their traditional indigenous cultures with that of the Greeks. They were inevitably attracted to the Greek religious system as well. Because of the overwhelming and unifying power of Hellenism, local tribal religions began to lose some of the distinctiveness of their culture. Eventually, the independent integrity of the local Near Eastern religious systems would die out entirely to this assimilation, though that process would not be complete until the arrival of the Romans.

The assimilation process encouraged by the Greek and Roman conquerors was not successful, however, under the strident monotheism of Israel. By the time the Greeks had come to the area, the Israelites had become localized in a region called Judea and increasingly referred to themselves as Judeans, from which we get the term Jew. One of the problems that Jews faced after the Greek conquest was that they were expected, like all foreign peoples, to make offerings to the Greek gods. Because they simply and adamantly refused to do so, a compromise was eventually reached that allowed the Jews to worship in their own unique manner and make donations to their temple in Jerusalem.

When the Romans took over, they imposed their own religious system, requiring that subjugated peoples make offerings to the Roman gods, including, eventually, the figure of the Roman emperor. The traditional ethnic religions that were organized around local gods could not compete against the cultural might and attractiveness of the Romans and their gods. Because the local religions were organized around the idea that many gods existed and powered the universe, it became easy for them to make offerings to the Roman gods as well. Like the Greeks before them, the Romans unified the region culturally, and local tribal nations and religions naturally integrated with that of the conquerors. Under the Romans, many indigenous communities lost most of their unique cultural and religious identities, succumbing to the imperial system and assimilating to it.

As with the Greeks, however, the monotheistic Jews could not assimilate into the Roman system. They were “grandfathered” by the Romans based on the policy of their Greek predecessors, and thus remained exempt from worshipping the Roman gods and emperors.

The Emergence of Christianity

We have noted how this period of Late Antiquity was a time of religious consolidation. The Romans had conquered many local peoples and their gods and assimilated them into the Roman system. But it was also a period of religious diffusion. The Roman system did not satisfy the religious and spiritual needs of many in the empire. As a result, new religious movements began to emerge.

One category of these new religions is sometimes referred to as “mystery cults,” such as Eleusinian mysteries. Mithraic mysteries (or Mithraism), and Orphic mysteries. Even the native Judeans, most of whom were steadfast in their monotheism, were profoundly affected by the powerful intellectual and cultural influence of Greece and Rome.

A number of movements began to develop within the monotheist framework that was later called Judaism. Pharisees, Saducees, Essenes, and other groups emerged during this time, including movements that expected a messianic figure to lead the Jews out from under the yoke of the Roman Empire. Adherents of these various groups argued with one another over their ideas and their positions on Jewish practice theology, and the meaning of scripture and God’s expectations for Jews and humanity at large.

One of the most significant new movements to emerge out of Judean monotheism formed around the leadership of an extraordinary Jewish preacher who eventually became known as “Jesus, the messiah”—“Jesus Christ.” Like the other monotheistic movements, this group refused to recognize the Roman gods or worship the emperor. We do not now exactly how and when it happened, but this group, now often referred to in scholarship as the Jesus movement, came to be recognized as distinct from other Judean monotheistic movements. This prevented it from being grandfathered by the empire as was Judaism, which had been previously recognized by the Greeks.

The Jesus movement grew quickly. It was eventually considered a threat to the empire and was brutally persecuted. Yet Christian monotheism, like the other monotheist movements, could not compromise the exclusive relationship with its singular God. The stubbornness of the early Christians illustrates what became a phenomenon of monotheism: an absolute requirement of undivided bond between monotheists and their God.

The ancient feeling of chosenness between a nation and its deity among polytheistic religions had become weakened when the local gods were so thoroughly defeated by the gods of Greece and Rome. Many local polytheists were able to make the transition to the dominant religious system, partly because of their aspiration to be accepted by the empire and eventually become Roman citizens. But the exclusive relationship between monotheists and their universal god never weakened.

The One Great God was always unique, different, and greater than any and all of the national gods, even the gods of the empire. Harassment and persecution by the forces of the empire did not prove the weakening of the monotheistic God. On the contrary, monotheists believed that God would bring about divine judgment against all the empires and redemption for the chosen few who followed the truth of their faith. God may be testing the chosen ones, even sometimes through great pain and suffering, but they would never be abandoned.

One final observation must be included here: the monotheistic requirement of exclusive relationship became experienced by some believers as a social truth. That is to say, people within monotheistic communities have tended to understand their chosenness not simply as a theological relationship, but also as a social and human value. they sometimes considered their special relationship with God to indicate or even epitomize their status as inherently better, more civilized or virtuous, than other among God’s human creations.

Perhaps as a people suffered for their exclusive loyalty to the One Great God, they came to feel that their special relationship made them inherently more godly and righteous than others. That association among some monotheists of chosenness with arrogance and self-importance would sometimes result in terrible abuse of others who were not considered part of God’s chosen community.

In any event, by the emergence of Christianity, a process that began in the ancient world had reached its natural conclusion. The notion of chosenness emerged in the ancient Near East, where ethnic polytheists naturally felt a unique relationship with their national gods. It was as if each nation’s god had chosen a single people for a unique, symbiotic relationship in which the people fed the god through sacrificial worship, and the god fed the people through providing fertility and protection.

In the earliest period, the Israelites were like other polytheistic peoples and had their own special bond with their God of Israel. That feeling of unique attachment continued among the Israelites even as they became believers in monotheism and the old symbiosis dissolved. No longer would God need the worship of believers, but believers would always need the worshipful relationship with God. Their organic sense of being chosen by the One Great God served also as a survival mechanism for Israelite monotheism in an overwhelmingly polytheistic world. By the Roman period and the decline and eventual extinction of ethnic polytheistic religions, that ancient sense of chosenness had become a trait that was deeply associated with belief in one God. It would become a defining trait of all subsequent expressions of monotheism.