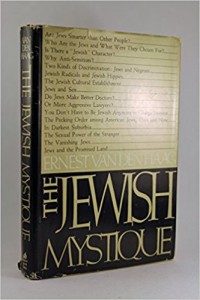

[First posted in 2014; Chapter 3 of our MUST READ/MUST OWN book: The Jewish Mystique by Ernest Van Den Haag.

Other posts from this book:

Reformatting, highlights, images added.—Admin1.]

——————————-

THE JEWS have invented more ideas, have made the world more intelligible, for a longer span and for more people, than any other group. They have done this directly and indirectly, always unintentionally, and certainly not in concert, but nevertheless comprehensively. The lives of us all in the West (as well as in Russia) and even of vast areas in the rest of the world have been strongly influenced, if not altogether shaped, by a view of human fate which is essentially Jewish in cast and origin. Jewish influence continues, not only through our common religious heritage, which clearly bears the marks of its Jewish origin, but also produced by Jewish scientists and scholars. To be sure, the Jewish view of the human career on earth—of its genesis, purpose, rewards, and pitfalls—has had its own career. Any creed that persists so long must be expected to change and develop. More remarkable, however, is the continuity of the core of the Jewish conception of human fate for so long at time.

Certainly Jewish groups, factions, movements, or persons do not hold the same ideas; nonetheless the persistence of some common beliefs leading to common practices and attitudes has been sufficient to leave a strong residue in the Jewish character. Attitudes are transmitted from generation to generation, and they are intensified when the external conditions which originally supported them remain unchanged. They become part of the character of the group.

Image from www.chabader.com

At first glance, the idea of a “Jewish character” may seem absurd or, worse, an anti-Semitic stereotype. Individual Jewish characters certainly differ. So do characteristics. And often Jews stand at opposite poles of almost any conceivable range of beliefs, practices, or positions. Some Jews are very poor, others are very rich. (Most are somewhere in between.) Certainly this influences their characters. Some are ruthlessly ambitious for material success—they want above all to “make it” wherever “the action is”—others are gentle and other-worldly. Some are sensualists, others puritans. some purvey the worst vulgarities of our culture in soap operas, musical comedies, TV, and general Kitsch, others are among the finest and most sensitive literary and social critics we have. Some (e.g. Norman Podhoretz’s Making It) combine intellectual gifts with success-oriented ambition, and perhaps with a renunciation of any identity other than that of succeeding—not an uncommon traumatic effect of sudden emancipation. Some are Communists, others are on the extreme right. (Most are in the “liberal” middle). Some are criminals, others judges. (The Jewish ambiguity toward the law and conscience is illustrated in the career of Judge Leibowitz of New York State. One of the most successful criminal lawyers the country has ever known, he defended notoriously vicious mobsters and killers. Elevated to the bench, he has become equally famous for his severity in sentencing the criminals he used to defend.) The Rosenbergs, atomic spies, were Jewish. So is Judge Kaufman, who sentenced them to death.

Do Jews have things in common then, other, than religion or descent, to transcend the many political, cultural, moral, psychological, social, economic, etc. differences that divide them and sometimes set one against the other?

I believe so. It is not, to be sure, any one thing. Rather there is a complicated network of overlapping and crisscrossing similarities and traits which occur and recur with greater than chance frequency among Jews. It is the resemblance that members of the same family may bear, even if some are nuns and others whores; some rich, others poor; some illiterate, others academicians; some atheists, others priests; some beautiful, others ugly. The similarity is not in what is done or thought, but in the way that it is done, thought, felt, believed, or expressed. And even this kind of family resemblance is a matter of frequency: it is not equally pronounced in all members of the group. The Jews obviously are not homogeneous. Yet the group is identifiably genetically, culturally, and psychologically by the relatively higher frequency of certain traits. Contradictory surface manifestations are produced by these traits, but the traits, more often than not, are the common source of these reactions.

There are three common elements deeply inherent in Judaism (the religion) and Jewishness (the character of the tribe and nation formed by the religion). The first of these elements is messianism; the second, intellectualism; the third, a moralistic-legalistic outlook.

From these common elements many seemingly contradictory ideas, actions, and styles can be derived. This includes the socialism, communism, atheism of some Jews and the conservatism and religious dogmatism of others; the civil disobedience of some and the insistence on lawful conduct of others; the intolerance of some—e.g., Communists, or sometimes, anti-Communists—and the tolerance of others; the puritanism of the rabbis, and Norman Mailer’s frenzied attempts to defy it and to free himself from it, or Philip Roth’s no less talented, or, at times, less obscene or frantic attempts to do so.

Roth, however, uses obscenity where it belongs: there is obscenity in his art, whereas there is art (often) in Mailer’s obscenity. Twho different ways—Roth’s more sublimated than Mailer’s—of defying one’s past? It seems likely. Mailer usually writes primitively idealized fantasies of himself—disguised as an Irishman—whereas Roth deals more directly and realistically with his past, trying to acknowledge and reabsorb what Mailer tries to deny by his disguise.

Unlike the other peoples of antiquity, the Jews not only believed in a paradise lost—the reign of Saturn to the Gentiles—but also in a paradise to be regained. This divine promise, to be redeemed by the Messiah—which Christianity elaborated, stressed and extended beyond the chosen people—underwent many modifications among bothy religious and nonreligious Jews, but it never was written off. Among the religious, it was felt that redemption depended on the Jews keeping their side of the bargain. Strict observance and interpretation of the Law became necessary because the Messiah would not come until all the Jews were virtuous and deserved paradise.

Judaism and Jewishness coalesced into an unending series of rules of conduct that identified Jews, made them cohere, set them apart, and made them suffer yet persist. For the promise was going to be redeemed. God was not going to go back on the bargain. And since the virtue of all the Jews was necessary to the descent of the Messiah from Heaven, it became the duty of every Jew to urge all other Jews to adhere to the Law and to their God. On this basis the intense community of the Jews was separated from all other peoples throughout their long history.

Emancipated Jews who, under the impact of the enlightenment, of industrialization, and of science, left their religion, secularized the idea of redemption as they did other Jewish values. Rationalism itself contains a promise of salvation: the idea of progress, the idea that by means of appropriate reforms and careful thought we ourselves can create the paradise that the Messiah was to establish. The idea that paradise can be achieved, whether by upholding or by overthrowing the law, is common to the religious Jew as well as to the anti-religious Jewish radical; it is an essentially Jewish idea.

To be sure, non-Jews can be, and are, Utopians, too. They are, knowingly or not, influenced by their Christian heritage, which contains the salvationist idea derived from Judaism. But the far greater frequency with which Jews dedicate themselves to messianic schemes is a direct result of the secularization of their traditional religious beliefs, which strengthen not only faith in salvation but also the conviction that salvation requires knowledge of some ineluctable law. Marxist theory, for instance, with its notions of historical necessity, can eaily take the place of talmudic scholarship. And often does.

As for justice, the Jews are the only people who have entered into a legal contract with their God—the covenant He made with Noah and with Abraham. Jews pray to their God, but also bargain and demand that He live up to His side of the agreement. And it is the law and the constant reinterpretation of it, the belief in justice and the practice of the intellectual legal version thereof, that has kept the Jews Jewish.

At first glance, it may seem unreasonable to derive either the messianic Utopianism which in religious or secular form has been a characteristic of Jews, or the moral drive for social justice and equality, from the prophetic Judaism in which they first appeared. Why should ideas pronounced 2500 years ago in a minor kingdom in the Middle East now influence Jews scattered in various places under the most diverse conditions? They would not, but for circumstances and institutions that kept these ideas alive.

When, after three unsuccessful rebellions, the emperor Hadrian banned the surviving Jews from their territory, many had already left. The more reasonable and moderate Jews, unable to forestall the rebellions of the Zealots and all too able to see the hopelessness of their attempt to defeat the Romans, had settled in various parts of the world. Some did not resist the influence of their new environment, but most followed the rabbinical injunction to keep apart, to live according to the Law which prohibited marriage with Gentiles and prevented more than casual relations with them.

According to the historian Josephus, as Jerusalem seemed about to fall to Vespasian’s legions (actually, it fell only later to those of Vespasian’s son, Titus), Rabbi Jochanaan ben Zakkai was sneaked out of the besieged city, hidden in a coffin. Rabbi Jochanaan was a leading Pharisee, that is, a moderate conservative; the Sadducees were the pro-hellenistic reform elements; and the Zealots were zealots in both politics and religious fundamentalism. (It is remarkable that these three elements—reform, conservative, and fundamentalist—can be seen once more in modern Judaism. But then circumstances have become similar: a secular, non-Jewish world beckons again.)

The leaders of the anti-Roman rebellion, themselves divided by factional strife, were Zealots, and the Pharisees had to lie low. Nonetheless, Rabbi Jochanaan surrendered to Vespasian in the name of the then actually powerless Pharisees, and in exchange obtained from him permission to open an academy of Hebraic studies. Vespasian was aware of the rabbi’s powerlessness, but he thought the formal surrender politically useful in Rome. It officially ended the war and conveniently classified the further fighting, at least temporarily, as a police action.

The rabbi’s institute, which flourished first in Japneh and later in Babylon, created a tradition that never wholly disappeared from Jewish life. It recreated Jewish identity and made it independent of territory, temple, and political organization: as invisible, and as strong and demanding, as the Jewish God. It achieved the transfer of legal and religious authority from God and His priests and prophets to the divine Law and its scholarly interpreters—the rabbis. These learned interpreters proceeded almost immediately to do three things that made possible the bond which has held the Jews together, cemented them into communities, and the communities, however scattered, into a nation. A nation without territory, government, or sovereignty—but still a nation. Owing to this tradition, cultivated by the rabbis, Jews continued to feel the yoke, the task, the moral mission of being Jews—of preserving themselves as such, and to the surprise, scorn, and at times hatred of the rest of the world, of refusing to become anything else.

This mission has been internalized deeply and pervasively, even by Jews who deny its raison de’être and regard talk of a chosen people and religion itself as so much superstition. Jews may call themselves humanists, or atheists, socialists, or communists; they may indifferently or passionately repudiate any reason whatsoever for remaining Jews; they may even dislike Jewishness and feel it—to use an apt metaphor—as a cross they have to bear. But rarely do they refuse to carry it, through they continually grumble and threaten to throw it off, and deny that they are getting anywhere, and haggle with God, the world, and their friends about the compensations they are to get. They will not be cheated out of the promised redemption, though the expectation is vague and ritualistic in some, altogether unconscious in others. They won’t give up being Jewish even when they consciously try to, when they change names, intermarry, and do everything they can to deny Jewishness. Yet they remain aware of it, and though repudiating it, they cling to it; they may repress it, but do act it out symptomatically. Their awareness of their Jewishness is shared by others simply because the denial is always ambivalent. Unconscious or not, at least some part of every Jew does not want to give up its Jewishness.

- The first of the three vital steps taken by the long line of rabbis who laid down the law to the Jews was to codify this LAW—the Old Testament. They decided what was, and what was not, Holy Writ. A body of history and prophecy was created, identical for all, which henceforth constituted the Jewish religion. The binding power of that codification stood the test of centuries. Indeed, the Jews, together in Jerusalem before the Diaspora, were divided into more sects and factions bitterly fighting each other than they were most of the time after their dispersal.

- Secondly, the rabbis codified the ritual of worship, which became identical for all Jews.

- Thirdly, and of immense importance, beyond worship the rabbis codified conduct which was to be inextricably linked to religion and to Jewishness. To be a Jew meant to follow numerous rules of conduct about eating, marrying, intercourse, children, education—about almost every detail of life. These rules of conduct served, together with ritual and belief, to set Jews apart from non-Jews, to keep them apart, and to keep them together. Not only were Jews warned against marrying non-Jews, they were prevented from even eating with them.

These three things separated the Jews from the rest of the world and provided a common center of belief and practice around which they could unify. The rabbis thus replaced the destroyed temple and its sacrifices of cattle only to impose a life of continuous self-sacrifice and ritual on the Jews. For to keep the minute rules and the comprehensive regulations was a heavy burden. Jews, for good measure, were enjoined to bear it joyfully.

Image from www.tabletmag.com

Individual practices, of course, required adaptation when circumstances changed. These were provided in continuous interpretations—in response to problems as they arose—given by a long line of rabbis. Interpretations were in turn reinterpreted and re-reinterpreted ad infinitum in every Jewish community.

And the community was just that. The synagogue was its center; the rabbi represented the community and decided what should be done with regard to the Gentile environment; he was the judge in religious and civil matters; often he was the physician; always he acted as “human relations counselor.” He was the final authority in the community. All this by virtue of his dedication to and knowledge of the Law.

This authority, derived from his study of the Law, contributed to the immense respect the Jews developed for learning. Together the Jewish communities did constitute a nation even though not sovereign or ruling over territory. Their internal affairs were left to them to regulate according to their Law (at least until emancipation) by their host nations. And their regulation had a distinct national style.

Such a long period of following the precepts laid down in the series of commentaries that shaped Jewish life and governed behavior and attitudes toward the outside world could not but be internalized. As it was transmitted from generation to generation, it left profound traces in individuals formed in these communities and resulted in characteristics which form a character—a character which remains in the modern secularized Jew who has abandoned the precept of which it is the precipitate.

None of the Jewish traits, however characteristic, is uniquely Jewish. Whether one considers attitudes toward the family, or money, or education, there are non-Jewish individuals who have identical attitudes and Jews who do not have “Jewish” attitudes. Nor is the totality of such traits in their relationship to each other—the character—altogether peculiar to the Jews. There are non-Jewish individuals whose total character is within the range of “Jewish” character types; their circumstances may have been such as to produce a character-type of the Jewish sort. And there are Jews with “un-Jewish” characters. Further, there is not one Jewish character, nor even one prototype, but a range of character types. This range overlaps with some others, in some aspects and segments—e.g., the Italian or Spanish character—but it does not fully coincide with any other. This entitles us to speak of those within it as “Jewish” character types. And secondly, the Jewish character types, those within the Jewish range—though also occurring within other groups, and not necessarily extending to all members of the Jewish group—occur within the Jewish group more frequently than outside. This, too, entitles us to speak of a specifically “Jewish” character.

Thus:

- The Jewish character includes a range of character types with individual variations, even though

- not all Jews have Jewish characters, and

- not all non-Jews lack Jewish characters, for,

- more Jews conform to one of the Jewish character types than do non-Jews.

That much to show that there can be, indeed there must be a Jewish character, and to show what it means if a character is attributed to a group. I have yet to describe at least some traits of that character [in following chapters of his book]. Let us see how history took a hand in forming them.