[Bart D. Ehrman chairs the Department of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. he is an authority on the history of the New Testament, the early church, and the life of Jesus. He has taped several highly popular lecture series for the Teaching Company and is the author of Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew and Lost Scriptures: Books that Did Not Make It into the New Testament. He lives in Durham, North Carolina.

This is on our MUST READ/MUST OWN category.—Admin1.]

———————————–

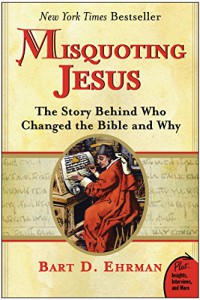

Misquoting Jesus:

The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why

In the inside cover of this book is this write up:

WHEN WORLD-CLASS BIBLICAL SCHOLAR Bart Ehrman began to study the texts of the Bible in their original languages he was startled to discover the multitude of mistakes and intentional alterations that had been made by earlier translators. In Misquoting Jesus, Ehrman tells the story behind the mistakes and changes that ancient scribes made to the New Testament and shows the great impact they had upon the Bible we use today. He frames the account with personal reflections on how his study of the Greek manuscripts made him abandon his once ultraconservative views of the Bible.

Since the advent of the printing press and the accurate reproduction of texts, most people have assumed that when they read the New Testament they are reading an exact copy of Jesus’s words or Saint Paul’s writings. And yet, for almost fifteen hundred years these manuscripts were hand copied by scribes who were deeply influenced by the cultural, theological, and political disputes of their day. Both mistakes and intentional changes abound in the surviving manuscripts, making the original words difficult to reconstruct. For the first time, Ehrman reveals where and why these changes were made and how scholars go about reconstructing the original words of the New Testament as closely as possible.

Ehrman makes the provocative case that many of our cherished biblical stories and widely held beliefs concerning the divinity of Jesus, the Trinity, and the divine origins of the Bible itself stem from both intentional and accidental alterations by scribes—alterations that dramatically affected all subsequent versions of the Bible.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

- The Beginnings of Christian Scripture

- The Copyists of the Early Christian Writings

- Texts of the New Testament: Editions, Manuscripts, and Differences

- The Quest for Origins: Methods and Discoveries

- Originals That Matter

- Theologically Motivated Alterations of the Text

- The Social Worlds of the Text

- Conclusion: Changing Scripture—Scribes, Authors, and Readers

————————————————–

Here’s are excerpts from Chapter 7, Subtitle: Jews and the Texts of Scripture

Jews and Christians in Conflict

One of the ironies of early Christianity is that Jesus himself was a Jew who worshiped the Jewish God, kept Jewish customs, interpreted the Jewish law, and acquired Jewish disciples, who accepted him as the Jewish messiah. Yet, within just a few decades of his death, Jesus’s followers had formed a religion that stood over-against Judaism. How did Christianity move so quickly from being a Jewish sect to being an anti-Jewish religion?

This is a difficult question, and to provide a satisfying answer would require a book of its own. Here, I can at least provide a historical sketch of the rise of anti-Judaism within early Christianity as a way of furnishing a plausible context for Christian scribes who occasionally altered their texts in anti-Jewish ways.

The last twenty years have seen an explosion of research into the historical Jesus. As a result, there is now an enormous range of opinion about how Jesus is best understood—as a rabbi, a social revolutionary, a political insurgent, a cynic philosopher, an apocalyptic prophet: the options go on and on. The one thing that nearly all scholars agree upon, however, is that no matter how one understands the major thrust of Jesus’s mission, he must be situated in his own context as a first-century Palestinian Jew. Whatever else he was, Jesus was thoroughly Jewish, in every way—as were his disciples. At some point—probably before his death but certainly afterward—Jesus’s followers came to think of him as the Jewish messiah. This term messiah was understood in different ways by different Jews in the first century, but one thing that all Jews appear to have had in common when thinking about the messiah was that he was to be a figure of grandeur and power, who in some way—for example, through raising a Jewish army or by leading the heavenly angels—would overcome Israel’s enemies and establish Israel as a sovereign state that could be ruled by God himself (possibly through human agency). Christians who called Jesus the messiah obviously had a difficult time convincing others of this claim, since rathe than being a powerful warrior or a heavenly judge, Jesus was widely known to have been an itinerant preacher who had gotten on the wrong side of the law and had been crucified as a low-life criminal.

To call Jesus the messiah was for most Jews complete ludicrous. Jesus was not the powerful leader of the Jews. He was a weak and powerless nobody—executed in the most humiliating and painful way devised by the Romans, the ones with the real power. Christians, however, insisted that Jesus was the messiah, that his death was not a miscarriage of justice or an unforseen event, but an act of God, by which he brought salvation to the world.

What were Christians to do with the fact that they had trouble convincing most Jews of their claims about Jesus? They could not, of course, admit that they themselves were wrong. And if they weren’t wrong, who was? It had to be the Jews. Early on in their history, Christians began to insist that Jews who rejected their message were recalcitrant and blind, that in rejecting the message about Jesus, they were rejecting the salvation provided by the Jewish God himself. Some such claims were being made already by our earliest Christian author, the apostle Paul. In his first surviving letter, written to the Christians of Thessalonica, Paul says:

For you, our brothers, became imitators of the churches of God that are in Judea in Christ Jesus, because you suffered the same things from your own compatriots as they did from the Jews, who killed both the Lord Jesus and the prophets, and persecuted us, and are not pleasing to God, and are opposed to all people. (I Thess. 2:14-15)

Paul came to believe that Jews rejected Jesus because they understood that their own special standing before God was related to the fact that they both had and kept the Law that God had given them (Rom. 10:3-4). For Paul, however, salvation came to the Jews, as well as to the Gentiles, not through the Law but through faith in the death and resurrection of Jesus (Rom. 3:21-22). Thus, keeping the Law could have no role in salvation; Gentiles who became followers of Jesus were instructed, therefore, not to think they could improve their standing before God by keeping the Law. They were to remain as they were—and not covert to become Jews (Gal. 2:15-16).

Other early Christians, of course, had other opinions—as they did on nearly every issue of the day! Matthew, for example, seems to presuppose that even though it is the death and resurrection of Jesus that brings salvation, his followers will naturally keep the Law, just as Jesus himself did (see Matt. 5:17-20). Eventually, though, it became widely held that Christians were distinct from Jews, that following the Jewish law could have no bearing on salvation, and that joining the Jewish people would mean identifying with the people who had rejected their own messiah, who had, in fact, rejected their own God.

As we move into the second century we find that Christianity and Judaism had become two distinct religions, which nonetheless had a lot to say to each other. Christians, in fact, found themselves in a bit of a bind. For they acknowledged that Jesus was the messiah anticipated by the Jewish scriptures; and to gain credibility in a world that cherished what was ancient but suspected anything “recent” as a dubious novelty, Christians continued to point to the scriptures—those ancient texts of the Jews—as the foundation of their own beliefs. This meant that Christians laid claim to the Jewish Bible as their own. But was not the Jewish Bible for Jews? Christians began to insist that Jews had not only spurned their own messiah, and thereby rejected their own God, they had also misinterpreted their own scriptures. And so we find Christian writings such as the so-called Letter of Barnabas, a book that some early Christians considered to be part of the New Testament canon, which asserts that Judaism is and always has been a false religion, that Jews were misled by an evil angel into interpreting the laws given to Moses as literal prescriptions of how to live, when in fact they were to be interpreted allegorically.

Eventually we find Christians castigating Jews in the harshest terms possible for rejecting Jesus as the messiah, with authors such as the second-century Justin Martyr claiming that the reason God commanded the Jews to be circumcised was to mark them off as a special people who deserved to be persecuted. We also find authors such as Tertullian and Origen claiming that Jerusalem was destroyed by the Roman armies in 70 C.E. as a punishment for the Jews who killed their messiah, and authors such as Melito of Sardis arguing that in killing Christ, the Jews were guilty of killing God.

. . . . Clearly we have come a long way from Jesus, a Palestinian Jew who kept Jewish customs, preached to his Jewish compatriots, and taught his Jewish disciples the true meaning of the Jewish law. By the second century, though, when Christian scribes were reproducing the texts that eventually became part of the New Testament, most Christians were former pagans, non-Jews who had converted to the faith and who understood that even though this religion was based, ultimately, on faith in the Jewish God as described in the Jewish Bible, it was nonetheless completely anti-Jewish in its orientation.

Anti-Jewish Alterations of the Text

The anti-Jewishness of some 2nd and 3rd-century Christian scribes played a role in how the texts of scripture were transmitted. One of the clearest examples is found in Luke’s account of the crucifixion, in which Jesus is said to have uttered a prayer for those responsible:

And when they came to the place that is called “The Skull,” they crucified him there, along with criminals, one on his right and the other on his left. And Jesus said, “Father, forgive them, for they don’t know what they are doing.” (Luke 23:33-24)

As it turns out, however, this prayer of Jesus cannot be found in all our manuscripts; it is missing from our earliest Greek witness (a papyrus called P75

Scholarly opinion has been divided on the question. Because the prayer is missing from several early and high-quality witnesses, there has been no shortage of scholars to claim that it did not originally belong to the text. Sometimes they appeal to an argument based on internal evidence.

Excerpts from CONCLUSION: CHANGING SCRIPTURE – Scribes, Authors, and Readers

In many ways, being a textual critic is like doing detective work. There is a puzzle to be solved and evidence to be uncovered. The evidence is often ambiguous, capable of being interpreted in various ways, and a case has to be made for one solution of the problem over another.

The more I studied the manuscript tradition of the New Testament, the more I realized just how radically the text had been altered over the years at the hands of scribes, who were not only conserving scripture but also changing it. To be sure, of all the hundreds of thousands of textual changes found among our manuscripts, most of them are completely insignificant, immaterial, of no real importance for anything other than showing that scribes could not spell or keep focused any better than the rest of us. It would be wrong, however, to say —as people sometimes do — that the changes in our text have no real bearing on what the texts mean or on the theological conclusion that one draws from them. . . . In some instances, the very meaning of the text is at stake, depending on how one resolves a textual problem.

. . . . The Bible is, by all counts, the most significant book in the history of Western civilization. And how do you think we have access to the Bible? Hardly any of us actually read it in the original language, and even among those of us who do, there are very few who ever look at a manuscript—let alone a group of manuscripts. How then do we know what was originally in the Bible A few people have gone to the trouble of learning the ancient languages (Greek, Hebrew, Latin, Syriac, Coptic, etc.) and have spent their professional lives examining our manuscripts, deciding what the authors of the New Testament actually wrote. In other words, someone has gone to the trouble of doing textual criticism, reconstructing the “original” text based on the wide array of manuscripts that differ from one another in thousands of places. Then someone has taken that reconstructed Greek text, in which textual decisions have been made (what was the original form of Mark 1:2 of Matt. 24:36? of John 1:18? of Luke 22:43-44? and so on) and translated it into English. What you read is that English translation—and not just you, but millions of people like you. How do these millions of people know what is in the New Testament? They “know” because scholars with unknown names, identities, backgrounds, qualifications, predilections, theologies, and personal opinions have told them what is in the New Testament. But what if the translators have translated the wrong text? [Ehrman then cites an example, the complicated problems with the King James Version alone].

Reality is never that neat, however, and in this case we need to face up to the facts.

[There’s much more to this concluding chapter but you get the picture . . . . best to secure a copy of the book, or borrow from our Sinai library; or download as ebook from amazon.com on any kindle app.]