[Featured here is the Introduction to the Must Read/Must Own Who are the REAL Chosen People? – by Reuven Firestone.—Admin1.]

—————————-

Choosing is something we do everyday, from our choice of what to wear in the morning to our decision at the end of the day to turn out the light rather than read that next chapter. Choosing is an ordinary act. We choose which seat we prefer on the bus, which route to take to work, which pen to use to write this paragraph. To choose is to select something freely and after consideration. When a person chooses, that person shows a preference for one thing over something else.

Choosing is also limiting. It is an act of identifying, of distinguishing, of separating. Although it is possible to choose “a few” rather than one, it is understood generally as singling out. The act of choosing immediately establishes a hierarchy. What is chosen is somehow different than the others. Usually, that difference represents a higher location on the ladder. It can also mean choosing a lower, of course, but that would be unintentional; when you make a choice, you hope you are choosing a winner. Being chosen, therefore, would appear to be a special and positive status that places the chosen over and above the non-chosen.

If being chosen is generally a good thing, consider being chosen by God.

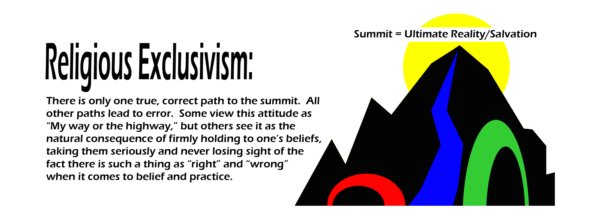

Jews, Christians, and Muslims — all three families of monotheistic religions—claim in one way or another to be God’s chosen community. Christian theologians have sometimes referred to God’s choosing for special favor as “election.” Whether called chosenness or election, the special nature of that divinely authorized status—its presumed superiority—has been glorified by religious civilizations when in positions of imperial power, and it has sustained religious communities suffering persecution. It has also made believers uncomfortable at times, especially in places where democracy, equality, and freedom are considered defining categories.

One important aspect of language is that every word has a range of meanings, often subtle, that affect its “personality.” When we use a word in speech, we are often affected unconsciously by that word’s subterranean tones and shades of meaning that have become associated with it through usage. The way a word has been used, say, in a famous speech or story provides shades of meaning that native speakers naturally pick up. Those nuances then enter the life of the word as it continues to be used in speech and in writing. This is very much the case with the word chosen. In his 1828 American Dictionary of the English Language, Noah Webster used biblical language to support most of his definitions. For his definition of choose, he includes, “To elect for eternal happiness; to predestinate to life.” He cites Matthew 22:14, “Many are called but few chosen,” and Mark 13:20, “For his elect’s sake, whom he hath chosen.” This is a big jump from choosing between your beige or navy slacks.

To be chosen, then, can have a range of meaning from the mundane to the holy, but in all cases it means to be singled out and preferred over others. The criteria for having been chosen could vary, from size and gender to wisdom and experience, but in a deep sense that permeates much or most of Western culture (and conveyed by Webster’s entry), having been chosen communicates a sense of something that is extraordinary, is transcendent, and entitles a reward. What is assumed in this sense of the term is that God has done the choosing and the reward is something that is unequaled, for what could possibly equal divinely ordained eternal happiness?

Those of us who live deeply within one of the three families of monotheism tend to accept the assumption of chosenness that is articulated within it at one level or another. It is good to believe that we live according to the will of God, and there is certainly nothing wrong about believing that we will receive divine reward for our religious activities or beliefs. For many of us, these beliefs represent deep and abiding aspects of who we are and what our purpose in life is. If we live entirely within our religious communities and with no interaction with people of other faith traditions, we would most likely not give the notion of being chosen a second thought. But we live in a multireligious world and bump against people and situations that sometimes challenge our religious assumptions. This is especially true when we hear believers in different faith traditions articulating the deep and abiding belief that they belong to God’s chosen. That would imply that we do not. Can more than one be chosen? What about those of other faiths who seem so certain? Can a religious tradition that expects or requires different beliefs or behaviors than our own also represent God’s will as surely as our own?

Unless we cut ourselves off entirely from interacting with anyone outside our religious communities, we cannot avoid this kind of cognitive dissonance. Knowing something about how and why the notion of chosenness has become so important in the monotheistic traditions can be useful because it can help us navigate between our own beliefs and those of others, and it can help us make sense of our own unique place in a complex world.

At some deep level there is a lot at stake in being chosen—or not being chosen. Webster’s definition shows that chosenness is associated with scripture, with happiness and even eternal life, and with a divine sense of order. It remains for us to try to understand how and why the concept of preference for one person or people over others became so important in religion.

We all embark on this quest by traveling through the histories of emergence of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam and the early interaction between the believers in these religious traditions. And we will examine the scriptures of each as well. The translations of the Hebrew Bible and the Qur’an are my own, although I based them on well-respected English translations. New Testament translations are derived from the Cambridge and Oxford Study Bibles. In an attempt to preserve the original flavor of these works spanning thousands of years of history the original sense of the language has been maintained whenever possible. This includes the use of masculine God language that may make some uncomfortable, but which I felt was necessary given the nature of this study.

Next: In the Beginning

Reader Comments