[First posted in 2013 with the following introduction:

If this was worth the typing, all the more it is worth reading! So prayerfully and hopefully, you—visitor to this website—will take the time to discover and truly understand the Jewish perspective on the Oneness and Unity of Israel’s God as stated in the opening line of the Shema. Find out why Israel has been regarded as the ‘Prophet of Monotheism’ and how its belief system has been belittled as ‘the minimum of religion’. Man is truly the inventor of religions and conceptualizations of God and what is common in all their thinking is reducing God down to man’s size and making Him manifest as one of His multi-faceted creations, talk about smallness of the mind. This is what makes the One True God of the Hebrew Scriptures all the more stand out as unique, according to His own Revelation. Indeed, there is none like You, O YHWH, God of Israel.

Commentary is from Pentateuch and Haftorahs, ed. Dr. J.H. Hertz; reformatting and highlights added. Translations: NIV/New International Version & EF/Everett Fox, The Five Books of Moses.—Admin1.]

———————————-

Image from guide.discoveronline.org

THE MEANING OF THE SHEMA

[NIV] Hear oh Israel, the LORD is our God, the LORD is One.’

[EF] Hearken O Israel: YHWH our God, YHWH is One!

These words enshrine Judaism’s greatest contribution to the religious thought of mankind. They constitute the primal confession of Faith in the religion of the Synagogue, declaring that—

- the Holy God worshipped and proclaimed by Israel is One;

- and that He alone is God,

- Who was, is, and ever will be.

That opening sentence of the Shema rightly occupies the central place in Jewish religious thought; for every other Jewish belief turns upon it: all goes back to it; all flows from it. The following are some of its far-reaching implications, negative and positive, that have been of vital importance in the spiritual history of man.

ITS NEGATIONS

Polytheism. This sublime pronouncement of absolute monotheism was a declaration of war against all—

- polytheism, the worship of many deities,

- and paganism, the deification of any finite thing or being or natural force.

It scornfully rejected —

- the star-cults and demon worship of Babylonia,

- the animal worship of Egypt,

- the nature worship of Greece,

- the Emperor worship of Rome,

- as well as the stone, tree, and serpent idolatries of other heathen religions with their human sacrifices, lustful rites, their barbarism and inhumanity.

Polytheism breaks the moral unity of man, and involves a variety of moral standards; that is to say, no standard at all. The study of Comparative Religion clearly shows that, in polytheism, ‘side by side with a High God of Justice and Truth, the cults of a goddess of sensual love, a god of intoxicating drink, or of thieves and liars, might be maintained’ (Farnell). It certainly is not the soil on which a high and consistent ethical system grows. This is true of even its highest forms, such as the heathenism of the Greeks. ‘The Olympian divinities merely copied and even exaggerated the pleasures and pains, the perfections and imperfections, the loftiness and baseness of life on earth. Man could not receive any moral guidance from them. The Greeks possessed nothing even remotely resembling a Decalogue to restrain and bind them’ (Kastein). Despite the love of beauty that characterized the Greeks, and despite their irridescent minds, they remained barbarians religiously and morally; and their race was held up by their pupils, the Romans of Imperial days, as the prototype of everything that was mendacious, cruel, grasping and unjust. The fruit of Greek heathen teaching is, in fact, best seen in the horrors of the arena, the wholesale crucifixions, and the unspeakable bestialities of these same pupils, the Romans of Imperial days.

Quite other were the works of Hebrew Monotheism.

- Its preaching of the One, Omnipotent God liberated man from slavery to nature; from fear of demons and goblins and ghosts; from all creatures of man’s infantile or diseased imagination.

- And that One God is One who ‘is sanctified by righteousness’, who is or purer eyes than to endure the sight of evil, or to tolerate wrong.

- This has been named ethical monotheism.

There may have been independent recognition of the unity of the Divine nature among some peoples; e.g. the unitary sun-cult of Ikhaton in Egypt, or some faint glimpses of it in ancient Babylon. But in neither of these systems of worship was it essentially ethical, completely transfused with the Moral Law, and holding moral conduct to be the beginning and end of the religious life. Likewise, moral thinking and moral practices had indeed existed from immemorial times everywhere; but the sublime idea that morality in something Divine, spiritual in its inmost essence—this is the distinctive teaching of the Hebrew Scriptures.

In Hebrew monotheism, ethical values are not only the highest of human values, but exclusively the only values of eternal worth.

‘There is none upon earth that I desire beside Thee,’

exclaims the Hebrew Psalmist. These words are but a poetic translation of the Shema in terms of religious experience.

Dualism. The Shema excludes dualism, any assumption of two rival powers of Light and Darkness, of the universe being regarded as the arena of a perpetual conflict between the principles of Good and Evil. This was the religion of Zoroaster, the seer of ancient Persia. His teaching was far in advance of all other heathen religions. Yet it was in utter contradiction to the belief in One, Supreme Ruler of the World, shaping the light, and at the same time controlling the darkness (Isa. XLV,7).

In the Jewish view, the universe, with all its conflicting forces, is marvellously harmonized in its totality; and, in the sum, evil is overruled and made a new source of strength for the victory of the good. ‘He maketh peace in His high places.’

Zoroastrianism is alleged by some to be responsible for many folklore elements in Jewish theology, especially for its angelology. But though later generations in Judaism did speak of Satan and a whole hierarchy of angels, these were invariably thought of as absolutely the creatures of God. To attribute Divine powers to any of these beings, and deem them independent of god, or in any way on par with the Supreme Being, would at all times have been deemed in Jewry to be wild blasphemy. It is noteworthy that the Jewish Mystics placed man—because he is endowed with free will—higher in the scale of spiritual existence than any mere ‘messenger’, which is the literal translation of the word angel, as well as of its Hebrew original, malakiym.

Pantheism. And the Shema excludes pantheism, which considers the totality of things to be the Divine. The inevitable result of believing that all things are divine, and all equally divine, is that the distinction between right and wrong, between holy and unholy, loses its meaning. Pantheism, in addition, robs the Divine Being of conscious personality. In Judaism, on the contrary, though God pervades the universe, He transcends it.

‘The heavens declare the work of Thy hands. They shall perish, but Thou shalt endure; yea, all of them shall wax old like a garment; as a vesture shalt Thou change them, and they shall pass away. But Thou art the selfsame, and Thy years shall have no end’ (Psalm CII,26-8).

The Rabbis expressed the same thought when they said:

‘The Holy One, blessed be He, encompasses the universe, but the universe does not encompass Him.’

And so far from submerging the Creator in His created universe, they would have fully endorsed the lines,

Though the earth and man were gone,

And suns and universes ceased to be,

And Thou wert left alone,

Every existence would exist in Thee’.

(Emily Bronte)

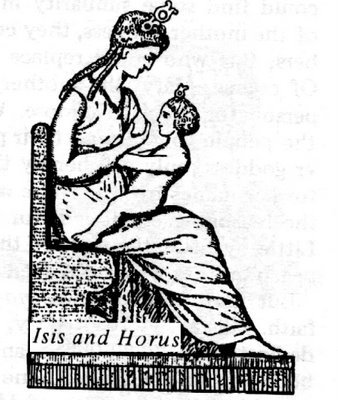

Image from piney.com

Belief in the Trinity. In the same way, the Shema excludes the trinity of the Christian creed as a violation of the Unity of God. Trinitarianism has at times been indistinguishable from tritheism; i.e. the belief in three separate gods. To this were added later cults of the Virgin and saints, all of them quite incompatible with pure monotheism.

Judaism recognizes no intermediary between God and man; and declares that prayer is to be directed to God alone, and to no other being in the heavens above or on earth beneath.

ITS POSITIVE IMPLICATIONS

Brotherhood of Man. The belief in the unity of the Human Race is the natural corollary of the Unity of God, since the One God must be the God of the whole of humanity. It was impossible for polytheism to reach the conception of One Humanity. It could no more have written in the 10th chapter of Genesis, which traces the descent of all the races of man to a common ancestry, than it could have written the first chapter of Genesis, which proclaims the One God as the Creator of the universe and all that is therein. Through Hebrew monotheism alone was it possible to teach the Brotherhood of Man; and it was Hebrew monotheism which first declared,

‘Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself’,

and

‘The stranger that sojourneth with you shall be unto you as the homeborn among you, and thou shalt love him as thyself’ (Lev. XIX,18,34).

Unity of the Universe. The conception of monotheism has been the basis of modern science, and of the modern world-view. Belief in the Unity of God opened the eyes of man to the unity of nature; that there is a unity and harmony in the structure of things, because of the unity of their Source’ (L. Roth).

- A noted scientist wrote; —‘The One, Sole God—conceived as the Supreme and Absolute Being who is the Source of all the moral aspirations of man—that conception of the Deity accustomed the human spirit to the idea of Reason underlying all things, and kindled in man the desire to learn that Reason’ (Dubois-Reymond).

- Likewise, A.N. Whitehead declares that the conception of absolute cosmic regularity its monotheistic in origin. And ‘every fresh discovery confirms the fact that in all Nature’s infinite variety there is one single Principle at work; that there is one controlling Power which—in the words of our Adon Olam hymn—is of no beginning and no end, existing before all things were formed, and remaining when all are gone’ (Haffkine).

Unity of History. And this one God—Judaism teaches—is the righteous and omnipotent Ruler of the universe. In polytheism, it was practically impossible to arrive at ‘the conception of a single Providence ruling the world by fixed laws; the multitude of divinities suggests the possibility of discord in the divine cosmos; and instills a sense of the capricious and incalculable in the unseen world’ (Farnell). Not so Judaism, with its passionate belief in a Judge of all the earth, who can and will do right. as early as the days of the Second Temple, the idea of the Sovereignty of God was linked with the Shema.

The Rabbis ordained that the words,

‘Hear, O Israel, the LORD is our God, the LORD is One,’

—should be immediately followed by “Blessed be His name, Whose glorious kingdom is for ever and ever”—the proclamation of the ultimate triumph of justice on earth. Jewish monotheism thus stresses the supremacy of the will of God for righteousness over the course of history: ‘One will rules all to one end—the world as it ought to be’ (Moore).

The Messianic Kingdom. The cardinal Jewish teaching of a living God who rules history has changed the heart and the whole outlook of humanity. Not only the hallowing of human life, but the hallowing of history flows from this doctrine of a Holy God, who is hallowed by righteousness.

It is only the Jew, and those who have adopted Israel’s Scriptures as their own, —

- who see all events in nature and history as parts of one all-embracing plan;

- who behold God’s world as a magnificent unity;

- and who look forward to that sue triumph of justice in humanity on earth which men call the Kingdom of God.

- And it is only the Jew, and those who have gone to school to the Jew, who can pray ‘May His kingdom come.’

Highest among the implications of the Shema is the passionate conviction of the Jew that the day must dawn —

- when all mankind will call upon the One God,

- when all the peoples will recognize that they are the children of One Father.

Nine hundred years ago, Rashi commented as follows on the six words of the Shema:

‘He Who now is our God and is not yet recognized by the nations as their God, will yet be the one god of the whole world. As it is written in Zephaniah III,9,

I will turn to the peoples a pure language, that they may all call upon the name of the LORD, to serve Him with one consent;

and it is said in Zechariah XIV,9,

And the LORD shall be king over all the earth; in that day shall the LORD be One, and His Name One.

A word must be added in regard to the two proof-texts cited by Rashi. The first,

‘I will restore to the peoples a pure language, that they may call upon the name of the LORD,’

—must be reckoned among the most remarkable utterances of the Prophets. It foretells a wonderful transformation of spirit that will come over the peoples of the earth. They are now only groping dimply after the true God, and stammering His praise. But the time will come when they shall adore Him with a full knowledge of Him; and with one consent (lit. ‘shoulder to shoulder’, i.e. without any superiority of one over the other), they will form a universal chorus to chant His praise. ‘The amazing thing about this prophecy is that it forsees the time when the curse of Babel will be removed from the children of men, and the confusion of tongues will end: one world-language, based on man’s moral and religious needs, will be the speech in the Kingdom of the spirit on earth’ (Sellin).

As to the words,

‘And the LORD shall be king over all the earth; in that day shall the LORD be One, and His Name One,’

they are combined with the Shema Yisroel in the Musaph Prayer of the New Year—one of the most solemn portions of the Jewish Liturgy. They also form the last sentence of the Oleynoo prayer, and thus end every statutory Jewish service—morning, afternoon, and evening. There could be no more fitting conclusion for the Jew’s daily devotions than this universalist hope of God’s Kingdom.

THE HISTORY OF THE SHEMA

The work of the Rabbis. Who unveiled to the masses of the Jewish people the spiritual wonders enshrined in the Shema? It is the immortal merit of the Rabbis in the centuries immediately before and after the common era, that these religious treasures did not remain the possession of the few, but became the heritage of the whole House of Israel. The recitation of the Shema was part of the regular daily worship in the Temple. They took it over to the Synagogue, and gave it central place in the morning and evening prayers of every Jew. We may judge the important part it played in the rabbinic consciousness from the fact that the whole Mishnah opens with the question, ‘From what hour is the evening Shema to be read?”

Image from perfectmemorials.com

It is the Rabbis who raised the six words to a confession of Faith; who ordained that they be repeated by the entire body of worshippers when the Torah is taken out on Sabbath and Festivals; in the Sanctification (Kedusha) on these sacred occasions; after the Neilah service, as the culmination of the great Day of Atonement; and in man’s last hour, when he is setting out to meet His Heavenly Father face to face. In this way, the Shema became the soul-stirring, collective self-expression of Israel’s spiritual being. But even in the private prayer of the individual Jew, the Rabbis spared no effort to enhance the solemnity of its utterance. It is to be said audibly, they ordained, the ear hearing what the lips utter; and its last word echod (‘One’) was to be pronounced with special emphasis. All thoughts other than God’s Unity must be shut out. It must be spoken with entire collection and concentration of heart and mind; the reading of the Shema may not be interrupted even to respond to the salutation of a king. If the words of the Shema are uttered devoutly and reverently–the Rabbis taught–they thrill the very soul of the worshipper and bring him a realization of communion with the Most High.

‘When men in prayer declare the Unity of the Holy Name in love and reverence, the walls of earth’s darkness are cleft in twain, and the face of the Heavenly King is revealed, lighting up the universe’ (Zohar).

The Shema and martyrdom. The unwearied national pedagogy of the Rabbis bore blessed fruit. The Shema became the first prayer of innocent childhood, and the last utterance of the dying. It was the rallying cry by which a hundred generations in Israel were welded together into one Brotherhood to do the will of their Father in heaven; it was the watchword of the myriads of martyrs who agonized and died for the Unity ‘as the ultima ratio of their religion’ (Herford). During every persecution and massacre, from the time of the Crusades to the wholesale slaughter of the Jewish population in the Ukraine in the years 1919 to 1921, Shema Yisroel has been the last sound on the lips of the victims. All the Jewish martyrologies are written around the Shema. The Jewish Teachers in medieval Germany introduced a regular Benediction for the recital of the Shema at the hour of ‘sanctification of the Name’; i.e. when a man is facing martyrdom. It is as follows:

‘Blessed art Thou, O LORD our God, King of the Universe, who hast sanctified us by Thy commandments and bade us to love Thee with all our heart and all our soul, and to sanctify Thy glorious and awful Name in public. Blessed art Thou, O Lord, Who sanctifiest Thy Name amongst the many.’

Numberless were the dire occasions when this Benediction was spoken. One instance will suffice. When the hordes of the Crusaders reached Xanten, near the Rhine (June 27,1096), the Jews of that place were partaking of their Sabbath-eve meal together. The arrival of the Crusaders meant, of course, certain death to them, and the meal was discontinued. But they did not leave the hall until the saintly R. Moses ha-Cohen first said Grace, enlarging the regular text with prayers appropriate to the awful moment. The Grace was concluded with the Shema.

Thereupon they went to the synagogue, where they all met with martyrdom. It is such happenings, which decimated the Jewish communities in the Rhine region by massacre and self-immolation to escape baptism, that caused the contemporary Synagogue poet, Kalonymos ben Yehudah, to sing;

‘Yea, they slay us and they smite,

Vex our souls with sore affright;

All the closer cleave we, LORD,

To thine everlasting word.

Not a line of all their Mass

Shall our lips in homage pass;

Though they curse, and bind, and kill,

The living God is with us still.

We still are Thine, though limbs are torn;

Better death than life forsworn.

From dying lips the accents swell,

“Thy God is One, O Israel.”;

The bridegroom answers unto bride,

“The LORD is God, and none beside,”

And, knit with bonds of holiest faith,

They pass to endless life through death.’

The reading of the Shema indeed fulfilled the promise of the Rabbis that it cloths man with invincible lion-strength. It endowed the Jew with the double-edged sword of the spirit against the unutterable terrors of his long night of suffering and exile.

Defence of the Unity. The Rabbis not only trained Israel to the understanding of the vital significance of the Divine Unity; they also defended the Jewish God-idea whenever its purity was threatened by enemies from without or within. They permitted no toying with polytheism, be its disguises ever so ethereal; they brooked no departure, even by a hair’s breadth, from the most rigorous monotheism; and rejected absolutely everything that might weaken or obscure it. The fight against idolatry and paganism begun by the Prophets was continued by the Pharisees. Abraham, the father of the Hebrew people, they taught, started on his career as an idol-wrecker. In legends, parables, and discourses, they showed forth the folly and futility of idol-worship, and pointed to the infamy and moral degradation evidenced by the Roman deification of the reigning Emperor. Josephus records that, when Caligula ordered the symbols of his divinity to be erected in the Temple at Jerusalem, tens of thousands of Jews declared their readiness to be trampled to death under the heels of the Roman cavalry, rather than suffer the Jewish belief in the Unity of God to be outraged.

‘In the world-wide Roman Empire, it was the Jews alone who refused the erection of statues and the paying of divine homage to Caligula. They thereby saved the honour of the human race, when all the other peoples slavishly obeyed the decree of the imperial madman’ (Fuerst).

The Rabbis defended the Unity of God against the Jewish Gnostics, those ancient heretics who blasphemed the God of Israel, ridiculed the Scriptures, and asserted a duality of Divine Powers. And they defended it against the Jewish Christians, who darkened the sky of Israel’s monotheism by teaching a novel doctrine of God’s ‘sonship’; by identifying a man, born of woman, with God; and by advocating the doctrine of a Trinity. Said a Palestinian Rabbi of the 4th century: ‘Strange are those men who believe that God has a son and suffered him to die. the God who could not bear to see Abraham about to sacrifice his son, but exclaimed “Lay not thine hand upon the lad,” would He have looked on calmly while His son was being slain and not have reduced the whole world to chaos!’

In the Middle Ages. Throughout the Middle Ages, the Jewish Teachers continued the religious education of the people begun in earlier centuries. They upheld the cause of pure Monotheism at the Religious Disputations in which thy were compelled to participate by the triumphant and all-powerful Church. That portion of their defence of Judaism which found expression in literary form, like the ‘Book of Victory’ (Sefer Nizzachon), is of lasting value. Such likewise is the book of Isaac Troki, a Polish Karaite of the 16th century, ‘the Defence of the Faith,’ which evoked the warm praise of Voltaire. Of special importance is the work of the Jewish philosophers, whose effort represents a distinct enrichment of the world’s religious thinking. Saadyah, Gabirol, Bachya, Hallevi, Maimonides purge the concept of God of all anthropomorphism, and vindicate the unity and uniqueness of Israel’s God-conception. Solomon Ibn Gabirol, renowned alike as philosopher and Synagogue poet, begins his Royal Crown with the words: ‘Thou art One, the first great Cause of all: Thou art One, and none can penetrate—not even the wisest heart—the unfathomable mystery of Thy Unity. Thou art One; Thy Unity can neither be lessened nor increased, for neither plurality nor change nor any attribute can be applied to Thee. Thou art One, but the imagination fails in any attempt to define or limit Thee. Therefore I said, “I will take heed to my ways, that I sin not with my tongue.”‘

In the present day. The long and arduous warfare begun by the Prophets and continued by the Rabbis is not yet ended. The unity of God has its antagonists int he present day, as in former ages. Even advanced non-Jewish writers on religion are, as a rule, but hesitating witnesses to the Unity of God; and liberal Christian theologians wax quite eloquent in depicting the amenities of life under polytheism. They plead that it helped to interfuse the whole life with ‘religion’; to intensify the ‘joy of life’ and delight int he world of nature; and that it made for religious tolerance.

On closer examination, these partisan claims collapse entirely. As for tolerance, even enlightened Greek polytheism permitted three of the greatest thinkers of the Periclean age—Socrates, Protagoras, and Anaxagoras—to be put to death on religious grounds. The Jews came into contact with Greek polytheism in its later stages. But neither Antiochus Epiphanes, who attempted to drown Judaism in the blood of its faithful children, nor Apion, the frenzied spokesman of the anti-Semites in Alexandria, displayed particular tolerance.

Again, the alleged interfusion of the whole of life with ‘religion’ under polytheism did not save the votaries of Greek polytheism from moral laxity, licentiousness and inhuman behavior both in war and peace. As to intensifying the ‘joy of life’—that ‘joy of life’, even among the Greeks, seems to have been the prerogative of the few. Thus, Greek society was broad-based on unrighteousness, i.e. on human slavery; and in Greece ‘the animated tool,’ as Aristotle defined the slave, was denied all human rights. It is, furthermore, difficult to see wherein the ‘joy of life’ consisted for the human sacrifices regularly offered by the heathen Semites and Slavs, Germans and Greeks. In regard to the last-named, it is not generally remembered that we find traces of human sacrifice throughout the Hellenic world, in the cult of almost every god, and in all periods of the independent Greek states. In the Roman Empire, this hideous accompaniment of polytheism continued till the fourth century of our present era; while in India the burning of widows was abolished only in the year 1840!

The other claims on behalf of polytheism are seen to be equally untenable. Delight in the world of nature was not confined to the polytheists. It could not have been alien to the people that produced the Song of Songs, and is therefore not the possession of heathenism alone. No less a scientist and thinker than Alexander von Humboldt was shown that the aesthetic contemplation of nature only began when the landscape was freed from its gods, and men could rejoice in nature’s own greatness and beauty.

Various secular writers on religion go far beyond modernist theologians in their depreciation of monotheism. Unlike those theologians, they do not halt between two opinions, and they know no hesitancies. Ernest Renan ascribed the rise of belief in One God to the desert surroundings of the early Hebrews. ‘The desert is monotheistic,’ he announced. He omitted, however, to explain why, if so, the other Semitic desert-dwellers had remained polytheists; or why the primeval inhabitants of the Sahara, Gobi and Kalahari deserts were not monotheists. Anti-Semites go further still. In order to belittle Israel’s infinite glory as the Prophet of Monotheism, they decry the Unity of God as ‘a bare, barren, arithmetical ideal as merely ‘the minimum of religion’. (It is strange that the alleged ‘minimum of religion’ should have given the Decalogue to the world; should have produced the Psalms, the book of devotion of civilized humanity; should have succeeded in shattering all idols, turning the course of history, and freeing the children of men from the stone heart of heathen antiquity.) Some of these anti-Semites contrast the bountiful abundance displayed by Greece in its hundreds of gods and goddesses, by India in its thousands of fantastic deities, with the one God of Israel. ‘Only one God—how mean, how meagre!’—they exclaim. It would serve no purpose to repeat further strictures on monotheism on the part of men who deem that, in attacking Jews, one need be neither logical nor fair; and that one may say anything of Jews and Judaism so long as it covers them with ridicule. But Truth is on the march; and the number of those thinkers is growing who recognize that ‘the Shema is the basis of all higher, ethical, spiritual religion; an imperishable pronouncement, reverberating to this day in every idealistic conception of the universe’ (Gunkel).

Conclusion. ‘It was undeniably a stroke of true religious genius—a veritable prompting by the Holy Spirit, —to select as Prof. Steinthal reminds us, out of the 5,845 verses of the Pentateuch this one verse (Deut. VI,4) as the inscription for Israel’s banner of victory.

Throughout the entire realm of literature, secular or sacred, there is probably no utterance to be found that can be compared in its intrinsic intellectual and spiritual force, or in the influence it exerted upon the whole thinking and feeling of civilized mankind, with the six words which have become the battle-cry of the Jewish people for more than twenty-five centuries’ (Kohler).