Image from momstransformed.blogspot.com

[First posted in 2014. A calming and conciliatory voice so badly needed in these troubled times and confusing age, Rabbi Harold S. Kushner has authored some bestsellers that we highly recommend:

- When Bad Things Happen to Good People,

- When All You Ever Wanted Isn’t Enough,

- Who Needs God,

His books are insightful and helpful to both Jew and Christian who wish to gain an understanding of God who is, after all, the God of all humanity except that sometimes, religions get in the way of that understanding. Among the Jewish voices that call for interfaith discourse, we are featuring Jews and Christians in Today’s World, the 11th chapter from his book To Life!, another MUST READ in our RESOURCES. After reading this one chapter, you will realize this book is a MUST OWN, whether you’re Jew or Christian or neither. Reformatting and highlights added.—Admin1.]

——————————————–

CHRISTIANS need to understand Judaism theologically, even if they never meet a live Jew. They need to understand what God had in mind when He entered into a Covenant with the Jewish people, and how that was changed by the birth and death of Jesus.

Jews don’t need to understand Christianity theologically, but we need to understand it practically, sociologically. We need to figure out what it means to live as Jews in a society where 90 percent of our neighbors are Christians, basing their religion partly on Hebrew Scriptures and partly on texts and traditions that go beyond them.

- How shall we understand Christianity?

- How shall we regard Jesus, who was born a Jew and is now regarded as the Divine Savior, Son of God, by so many of our neighbors?

- And how shall we understand the historical developments that saw Christianity begin as a tiny sect within Judaism and go on to become the religion of half the world?

If we worship the same God and revere the same Bible, why are so many people sitting in their section of the bleachers and so few in ours?

Let me emphasize that this chapter is not a scholarly history of Christianity or an introduction to its theology. Neither is it an attempt to suggest to a Christian reader of this book that his beliefs may be wrong. It is a Jewish perspective on the phenomenon of Christianity emerging from Jewish roots.

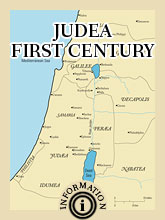

We begin with the historical setting in which Christianity arose. What we now think of as the first century of the Christian era, the century in which Jesus lived and died, was a time of messianic ferment in the Roman province of Judea.

- In biblical times, that land had been called Israel.

- It would later be called Palestine, as the Romans tried to erase the memory of a Jewish presence by naming it after the seafaring Mediterranean people who had briefly inhabited the coast around 1100 B.C.

- Since 1948, it has been called Israel again.

The Roman rulers were cruel and greedy, collecting outrageous sums in takes to finance their empire and putting to death anyone suspected of being a potential troublemaker. Times were so hard that people believed God would imminently intervene to save them as He had in Egypt. They compared the pain of their situation to the travail of a woman giving birth; the pains are most intense just before delivery. They not only prayed for a messianic redeemer; they expected his arrival daily.

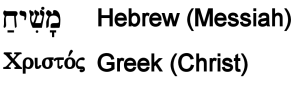

The Hebrew word Messiah was originally a synonym for the king. The word means “king,” the one who was crowned by having the anointing oil poured on his head. (It literally means “the anointed one,” as does the Greek christos.). In biblical times, the Messiah for whom the people prayed was a just and honest king, more decent and effective than the one currently ruling them. Like all legitimate kings of Israel, he would be a descendant of King David, but he was not seen as having any superhuman powers. The prophet Isaiah describes him this way:

There shall come forth a shoot from the stump of Jesse [David’s father], and a branch shall grow out of its roots. And the spirit of the Lord shall be upon him, the spirit of wisdom and understanding, the spirit of counsel and might, the spirit of knowledge and the fear of the Lord. He shall not judge by what his eyes see, or decide by what his ears hear. With righteousness shall he judge the poor, and decide with equity for the meek of the earth.[Isaiah 11:1-4]

In other words, if we could just have a good, honest, inspired king, he would solve all our problems.

Eight hundred years after Isaiah spoke, the land of the Jews, like most of Europe and the Middle East, had become part of the Roman Empire. Now it was not enough to hope for a fair and honest ruler. Before a Jewish king could begin judging the poor righteously, he first had to chase away the Roman occupier, and that would require divine intervention on a miraculous scale. Now the Messiah had to be a superhuman figure—not the Son of God or the Redeemer from Sin (those are non-Jewish concepts introduced by early Christianity), but a person capable of leading the Jews to victory over the greatest military force in the world.

It was into this setting that Jesus of Nazareth was born. We don’t know anything for certain about his life. All we know about him comes from accounts written two generations later by people who believed that he was the Messiah and wanted to persuade others of that fact. But the following seems to be a plausible outline of his career:

He was born into a working-class family in Nazareth, a rural city in Galilee in northern Israel, far from the centers of learning and political power. Later Christian sources would add an account of his parents traveling to Bethlehem when he was due to be born, because Bethlehem was King David’s hometown and there was a tradition that the Messiah would come from there. But many Jewish and Christian scholars doubt that.

The young man (whose Hebrew name meant “God will save”) grew up to be a compelling and charismatic teacher and preacher, offering a view of Judaism (shared with many of the leading Jewish teachers of that time) that emphasized inward perfection more than external performance. Albert Schweitzer has suggested that the central idea in Jesus’ teaching was the conviction that the world was going to end very soon, probably in his lifetime. Everyone, therefore, needed to put aside all other concerns (getting married, earning a living) and prepare for the End of Days and the Judgment. That is why he preached an ethic (turn the other cheek, don’t hate or covet, don’t worry about your parents or family), that people might be able to follow in the short run but not for a lifetime.

Many responded to his message and his effective way of presenting it, and he began to develop a reputation and a following. Because he had this gift of making people want to follow him and do what he asked them to do, some people began to wonder if he might be the heaven-sent redeemer.

What follows is a personal, somewhat unconventional but plausible interpretation of the Gospel accounts in the New Testament. One day, someone asked him,

“Master, shall we pay our taxes to Rome?” In other words, “Shall we rise in revolt?” Stopping the flow of taxes was the traditional way of beginning a revolt. Jesus held up a coin and asked, “Whose likeness is this coin?” “Caesar’s,” the people answered. “Then render unto Caesar what is Caesar, and unto God what is God’s.”

That is, pay your taxes; the revolution I have come to call for is a spiritual one, not a political one. In the next verse (Matthew 22:22), “When they heard these words, they marvelled and left him and went on their way.” I take that to mean that they were disappointed that he did not promise to expel the Romans, and stopped following him.

Shortly after that, Jesus and a few disciples made their way to Jerusalem for Passover. As we remember from our discussion of the pilgrim festivals, every Jew who was physically able to do so would travel to Jerusalem to celebrate Passover at the Temple. I can imagine that this made the Roman authorities nervous. First of all, the streets were crowded with tens of thousands of pilgrims who might easily become an uncontrollable mob.

Second, the message of Passover, a message of divinely assisted liberation, was likely to inspire some hotheaded Jews to rise in revolt. I can believe that the Roman authorities adopted a policy of “crack down first and investigate later.

A day or two later, Jesus was put to death by crucifixion, a particularly cruel form of execution. It is very clear from all accounts that he was killed by the Romans, not by Jews, and that he was one of many people crucified by the Romans in Judea. After his death, his closest friends and followers began to see visions of him (it is not unusual for people to dream or daydream about someone they loved and lost; it has happened to me) and began to believe that he had risen from the dead and must indeed have been the Messiah.

Paul, who had never met Jesus but became convinced of his divine mission, found the non-Jewish world more receptive. He brilliantly combined the strenuous moral teachings of the Jewish tradition with familiar elements of pagan religion that had not been part of Jesus’ original message—the leader, born of a divine father and human mother, who dies and comes back to life. Perhaps out of conflicts within his own personality, he crafted the very non-Jewish notion of Original Sin, that because none of us is perfect, we are all condemned to hell and only the willing sacrifice of a perfect, sinless man (God come down in human form) can save us.

- no dietary laws,

- no Sabbath observance,

- no need to circumcise male converts.

But it was not that easy to be a Christian in the first or second century. (Remember all those movies where Christians are thrown to the lions to entertain Roman audiences?)

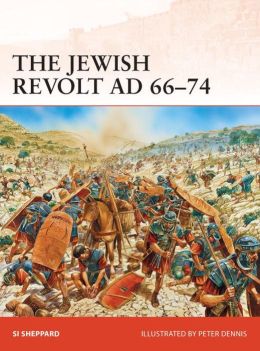

Part of the answer lies in the fact that in the year 67 and again in the year 135 (the Bar Kochba rebellion), the Jews rose in revolt against Rome, seeking their freedom. Both times, they fought heroically, and both revolts were put down with great loss of life. The Romans were so angry at having to send troops to put down these revolts that they tried to crush Judaism in Judea, forbidding its teaching or practice. That was when they destroyed the Second Temple and changed the name of Judea to Palestine, and that is why the definitive Talmud, the commentary on how the laws of the Torah were to be lived, was written in Babylonia rather than in Judea. As a result, Judaism was physically and emotionally depleted at home, and had the image of being a nation of losers and troublemakers throughout the empire.

The people of the Roman Empire did not have to choose between Judaism and Christianity. They had a third option: remaining pagans, worshiping the nature-gods of the old religions. Why did so many of them choose Christianity? Having the emperor designate it the official religion of the empire certainly helped. But I believe that there is something in the human soul that responds to the call to righteousness, the summons to be moral. We intuitively know that we are different from the animals, and that this difference is located in our ability to know right from wrong. We want to believe that our moral choices are taken seriously, and only biblical monotheism, whether in its Jewish or its Christian formulation, offered that message.