[If you haven’t read the prequel to this, please go to:

MUST READ/MUST HAVE: The Five Books of Moses by Everett Fox – 1

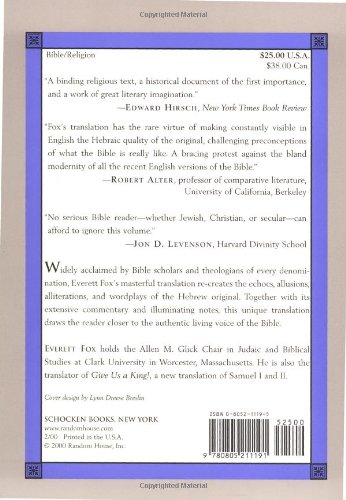

To encourage our visit ors to get a copy of the book recommended here for their personal library, we are featuring excerpts from TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE and ON THE NAME OF GOD AND ITS TRANSLATION. When you browse a bookstore for books you’re not familiar with, it is always good to check out the author’s background, his works, and if there is enough time to read through Introduction/Preface/Prologue and sometimes even Epilogue/Conclusion; these ‘bookends’ provide a window into what to expect from any book.

ors to get a copy of the book recommended here for their personal library, we are featuring excerpts from TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE and ON THE NAME OF GOD AND ITS TRANSLATION. When you browse a bookstore for books you’re not familiar with, it is always good to check out the author’s background, his works, and if there is enough time to read through Introduction/Preface/Prologue and sometimes even Epilogue/Conclusion; these ‘bookends’ provide a window into what to expect from any book.

What drew us to Everett Fox’s translation is its literary merit, first and foremost—quite a big difference in the translation from what we had been so used to; it gave us a ‘feel’ of reading in English what we might have read in the original language, if we could read Hebrew. Names were different. And now that our Sinaite focus is on the Name of God and its use in English versions or translations, this book clinches it for us. We wish, however, that just like the CJB/Complete Jewish Bible by David Stern who simply superimposed Hebrew terms and names on the English equivalent, that Fox had used more Hebrew words but. . . obviously we can’t have it all. The translator does explain why he didn’t go far enough with using Hebrew terms. And so, we are content with what we can have, for now, until another better one surfaces and we move on. Literary critics of biblical language however agree that Everett Fox and Robert Alter’s versions which share the same title, The Five Books of Moses, are two of the best and most reliable versions available today.—Admin1.]

————————————————-

The title page:

THE FIVE BOOKS OF MOSES

Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy

A NEW TRANSLATION WITH INTRODUCTIONS, COMMENTARY, AND NOTES BY EVERETT FOX

Illustrations by Schwebel

Publisher: SCHOCKEN BOOKS, New York

Copyright 1983,1986,1990,1995 by Schocken Books Inc.

Illustrations copyright 1997 by Schwebel

———————————————

CONTENTS

Translator’s Preface

Acknowledgements

On the Name of God and Its Translation

Guide to the Pronunciation of Hebrew Names

To Aid the Reader of Genesis and Exodus

—————————————————

GENESIS: AT THE BEGINNING

On the Book of Genesis and Its Structure

PART I: THE PRIMEVAL HISTORY (I-II)

THE PATRIARCHAL NARRATIVES

PART II: AVRAHAM (12-25:18)

PART III: YAAKOV (25:19-36:43)

PART IV: YOSEF (37-50)

——————————————————-

EXODUS: NOW THESE ARE THE NAMES

On the Book of Exodus and Its Structure

PART I: THE DELIVERANCE NARRATIVE (1-15:21)

THE EARLY LIFE OF MOSHE AND RELIGIOUS BIOGRAPHY

ON THE JOURNEY MOTIF

MOSHE BEFORE PHARAOH: THE PLAGUE NARRATIVE (5-11)

PART II: IN THE WILDERNESS (15:22-18:27)

PART III: THE MEETING AND COVENANT AT SINAI (19-24)

ON COVENANT

ON BIBLICAL LAW

PART IV: THE INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE DWELLING AND THE CULT (25-31)

PART V: THE COVENANT BROKEN AND RESTORED (32-34)

PART VI: THE BUILDING OF THE DWELLING (35-40)

APPENDIX: SCHEMATIC FLOOR PLAN OF THE DWELLING

To Aid the Reader of Leviticus-Numbers- Deuteronomy

——————————————————-

LEVITICUS: NOW HE CALLED

On Translating Leviticus

On the Book of Leviticus and Its Structure

PART I: THE CULT AND THE PRIESTHOOD (1-10)

ON ANIMAL SACRIFICE

PART II: RITUAL POLLUTION AND PURIFICATION (11-17)

ON THE DIETARY RULES

ON THE RITUAL POLLUTION OF THE BODY

PART III: HOLINESS (18-26)

AN APPENDED CHAPTER (27)

———————————————–

NUMBERS: IN THE WILDERNESS

On the Book of Numbers and Its Structure

PART I: THE WILDERNESS CAMP (1-10)

PART II: THE REBELLION NARRATIVES (11-25)

ON BIL’AM

PART III: THE PREPARATIONS FOR CONQUEST (26-36)

————————————————————–

DEUTERONOMY: THESE ARE THE WORDS

On the Book of Deuteronomy and Its Structure

PART I: HISTORICAL REVIEW (1-4:43)

PART II: OPENING EXHORTATION (4L44-11:32)

PART III: THE TERMS OF THE COVENANT (12-28)

PART IV: CONCLUDING EXHORTATION (29-30)

PART V: FINAL MATTERS (31-34)

Suggestions for Further Reading

—————————————————-

[Excerpts from . . . ]

TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE

. . . read the Bible as though it were something entirely unfamiliar, as though it had not been set before you ready-made. . . . Face the book with a new attitude as something new . . . . Let whatever may happen occur between yourself and it. You do not know which of its sayings and images will overwhelm and mold you . . . . But hold yourself open. Do not believe anything a priori; do not disbelieve anything a priori. Read aloud the words written in the book in front of you; hear the word you utter and let it reach you.

—-adapted from a lecture of Martin Buber, 1926

THE PURPOSE OF THIS WORK IS TO DRAW THE READER INTO THE WORLD OF THE HEBREW BIBLE through the power of its language. While this sounds simple enough, it is not usually possible in translation. Indeed, the premise of almost all Bible translations, past and present, is that the “meaning” of the text should be conveyed in as clear and comfortable a manner as possible in one’s own language. Yet the truth is that the Bible was not written in English in the twentieth or even the seventeenth century; it is ancient, sometimes obscure, and speaks in a way quite different from ours. Accordingly, I have sought here primarily to echo the style of the original, believing that the Bible is best approached, at least at the beginning, on its own terms. So I have presented the text in English dress but with a Hebraic voice.

The result looks and sounds very different from what we are accustomed to encountering as the Bible, whether in the much-loved grandeur of the King James Version or the clarity and easy fluency of the many recent attempts. There are no old friends here; Eve will not, as in old paintings, give Adam an apple (nor will she be called “Eve”), nor will Moses speak of himself as “a stranger in a strange land,” as beautiful as that sounds. Instead, the reader will encounter a text which challenges him or her to rethink what these ancient books are and what they mean, and will hopefully be encouraged to become an active listener rather than a passive receiver.

This translation is guided by the principle that the Hebrew Bible, like much of the literature of antiquity, was meant to be read aloud, and that consequently it must be translated with careful attention to rhythm and sound. The translation therefore tries to mimic the particular rhetoric of the Hebrew whenever possible, preserving such devices as repetition, allusion, alliteration, and wordplay. It is intended to echo the Hebrew, and to lead the reader back to the sound structure and form of the original.

Such an approach was first espoused by Martin Buber and Franz Rosenzweig in their monumental German translation of the Bible (1925-1962) and in subsequent interpretive essays. The Five Books of Moses is in many respects an offshoot of the Buber-Rozenweig translation (hereafter abbreviated as B-R). I began with their principles: that translations of individual words should reflect “primal” root meanings, that translations of phrases, lines, and whole verses should mimic the syntax of the Hebrew, and that the vast web of allusions and wordplays present in the text should be somehow perceivable in the target language (for a full exposition in English, see now Buber and Rozenzweig 1994). In all these areas I have taken a more moderate view than my German mentors, partly because I think there are limitations to these principles and partly because recent scholarship points in broader directions. As a result, my translation is on the whole less radical and less strange in English than B-R was in German. This, however, does not mean that it is less different from conventional translations, or that I have abandoned the good fight for a fresh look at the Bible’s verbal power.

Buber and Rosenzweig based their approach on the Romantic nineteenth-century notion that the Bible was essentially oral literature written down. In the present century there have been Bible scholars who have found this view attractive; on the other hand, there has been little agreement on how oral roots manifest themselves in the text. One cannot suggest that the Bible is a classic work of oral literature in the same sense as the Iliad or Beowulf. It does not employ regular meter or rhyme, even in sections that are clearly formal poetry. The text of the Bible that we possess is most likely a mixture of oral and written materials from a variety of periods and sources, and recovering anything resembling original oral forms would seem to be impossible. This is particularly true given the considerable chronological and cultural distance at which we stand from the text, which does not permit us to know how it was performed in ancient times.

A more fruitful approach, less dependent upon theories whose historical accuracy is unprovable, might be to focus on the way in which the biblical text, once completed, was copied and read. Recent research reveals that virtually all literature in Greek and Roman times—the period when the Hebrew Bible was put into more or less the form in which it has come down to us (but not the period of its composition)—was read aloud. This holds for the process of copying or writing, and also, surprisingly, for solitary reading. As late as the last decade of the fourth century, Saint Augustine expressed surprise at finding a sage who read silently. Such practices and attitudes seem strange to us, for whom the very definition of a library, for instance, is a place where people have to keep quiet. But it was a routine in the world of antiquity, as many sources attest.

So the Bible, if not an oral document, is certainly an aural one; it would have been read aloud as a matter of course. But the implications of this for understanding the text are considerable. The rhetoric of the text is such that many passages and sections are understandable in depth only when they are analyzed as they are heard. Using echoes, allusions, and powerful inner structures of sound, the text is often able to convey ideas in a manner that vocabulary alone cannot do. A few illustrations may suffice to introduce this phenomenon to the reader; it will be encountered constantly throughout this volume.

[Several paragraphs to illustrate samples of previous translations; and the difference when the Hebrew original is translated with sound or aural effect in mind, as opposed to simply being read.]

2

Excerpt: Once the spokenness of the Bible is understood as a critical factor in the translation process, a number of practical steps become necessary which constitute radical changes from past translation practices. Buber and Rosenzweig introduced three major innovations into their work: the form in which the text is laid out, the reproduction of biblical names and their meanings, and the “leading-word” technique by means of which important repetitions in the Hebrew are retained in translation.

3

Excerpt: Reading the Bible in the literary, rhetorical manner . . . is grounded in certain assumptions about the text. The Five Books of Moses stays close to the basic “masoretic” text-type of the Torah, that is, the vocalized text that has been with us for certain for about a millennium. Deviations from that form, in the interest of solving textual problems, are duly mentioned in the Notes. In following the traditional Hebrew text, I am presenting to the English reader an unreconstructed book, but one whose form is at least verifiable in a long-standing tradition. This translation, therefore, is not a translation of some imagined “original” text, or of the Torah of Moses or Solomon’s or even Jeremiah’s time. These documents, could they be shown to have existed for certain or in recognizable form, have not been found, and give little promise of ever being found. The Five Books of Moses is, rather, a translation of the biblical text as it might have been known in the formative, postbiblical period of Judaism and early Christianity (the Roman era). As far as the prehistory of the text is concerned, readers who have some familiarity with biblical criticism will note that in my Commentary I have made scant reference to the by-now classic dissection of the Torah into clear-cut prior “sources” (designated J,E,P, and D by the Bible scholars of the past century). Such analysis has been dealt with comprehensively by others . . . . In addition, it remains a theoretical construct, and the nature of biblical texts militates against recovering the exact process by which the Bible came into being. In any event, virtually all the standard introductions of the Bible deal with this topic; beyond these, readers may find Friedman (1989) of particular clarity and usefulness.

Given the text that i am using, what has interested me here is chiefly the final form of the Torah books, how they fit together as artistic entities, and how they have combined traditions to present a coherent religious message. This was surely the goal of the final “redactor(s),” but it was not until recently a major goal of biblical scholars. While, therefore, I am not committed to refuting the tenets of source criticism in the strident manner of Benno Jacob and Umberto Cassuto, I have concentrated in this volume on the “wholeness” of the biblical texts, rather than on their growth out of fragments. My commentary is aimed at helping the reader to search for unities and thematic development.

At the same time, in recent years I have found it increasingly fascinating to encounter the text’s complex layering. It appears that every time a biblical story or law was put in a new setting or redaction, its meaning, and the meaning of the whole, must have been somewhat altered. A chorus of different periods and concerns is often discernible, however faintly. Sometimes these functions to “deconstruct” each other, and sometimes they actually create a new text. In offering a rendition that does not try to gloss over stylistic differences, I hope that this book will make it possible for the inquisitive reader to sense that process at work. . . .

5

Excerpts: Over the past two decades, there has been an explosion of “literary” study of the Bible. Numerous scholars have turned their attention to the form and rhetoric of the biblical text, concentrating on its finished form rather than on trying to reconstruct history or the development of the text. Such an approach is hardly new. Already in late antiquity, Jewish interpretation of the Bible often centered around the style and precise wording of the text, especially as heard when read aloud. Similarly, the medieval Jewish commentators of Spain and France showed great sensitivity to the linguistic aspects of the Bible. In both cases, however, no systematic approach was developed; literary interpretation remained interwoven with very different concerns such as homiletics, mysticism, and philosophy.

It has remained for twentieth century scholars, reacting partly against what they perceived to be the excessive historicizing of German Biblical scholarship, to press for a literary reading of the Bible. . . . [This translation] is akin to many of these efforts, and has benefited directly from them. Although I began my work independently of the literary movement, I have come to feel a kinship with it, and regard my text as one that may be used to study the Bible in a manner consistent with its findings. At the same time, I am not committed to throwing out historical scholarship wholesale. It would be a mistake to set up the two disciplines in an adversarial relationship, as has often been done. The Hebrew Bible is by nature a complex and multi-faceted literature, in both its origins and the history of its use and interpretation. No one “school” can hope to illuminate more than part of the whole picture, and even then, one’s efforts are bound to be fragmentary. Probably, only a synthesis of all fruitful approaches available into a fully interdisciplinary methodology will provide a satisfactory overview of the biblical text . . . In this respect, approaching the Bible is analogous to dealing with the arts in general, where a multitude of disciplines from aesthetics to the social and natural sciences is needed to flesh out the whole. I hope [this] will make a contribution toward this process, by providing an English text, and an underlying reading of the Hebrew, that balances what has appeared previously. . . .

6

Excerpts: To what extent can any translation of the Bible be said to be more “authentic” than another? Because of lack of information about the various original audiences of our text, the translator can only try to be as faithful as the information will allow. This is particularly true where a work as universally known as the Bible is concerned. Even if the precise circumstances surrounding its writing and editing were known, the text would still be affected by the interpretations of the centuries. It is as if a Beethoven symphony were to be performed on period instruments, using nineteenth-century performance techniques: would it still sound as fresh and radical to us as it did in Beethoven’s own day? Thus I would suggest that it is almost impossible to reproduce the Bible’s impact on its contemporaries; all that the translator can do is to perform the task with as much honesty as possible, with a belief in one’s artistic intuition and a consciousness of one’s limitations.

Yet how are we to distinguish the point where explication ends and personal interpretation begins? From the very moment of the Bible’s editing and promulgation, there began the historical process of interpretation, a process which has at times led to violent disagreement between individuals and even nations. Everyone who has ever taken the Bible seriously has staked so much on a particular interpretation of the text that altering it has become close to a matter of life and death. Nothing can be done about this situation, unfortunately, and once again the translator must do the best he or she can. Art, by its very nature, gives rise to interpretation—else it is not great art. The complexity and ambiguity of great literature invites interpretation, just as the complexities and ambiguities of its interpreters encourage a wide range of perspectives. The Hebrew Bible, in which very diverse material has been juxtaposed in a far-ranging collection spanning centuries, rightly or wrongly pushes the commentator and reader to make inner connections and draw overarching conclusions. My interpretations in this book stem from this state of affairs. I have tried to do my work as carefully and as conscientiously as I can, recognizing the problems inherent in this kind of enterprise. I hope the result is not too far from what the biblical editors had intended.

My ultimate goal in this volume has been to show that reading the Hebrew Bible is a process, in the same sense that performing a piece of music is a process. Rather than carrying across (“translating”) the content of the text from one linguistic realm to another, I have tried to involve the reader in the experience of giving it back (“rendering”), of returning to the source and recreating some of its richness. My task has been to present the raw material of the text as best as I can in English, and to point out some of the method that may be fruitfully employed in wrestling with it.

Buber and Rosenzweig translated the Bible out of the deep conviction that language has the power to bridge worlds and to redeem human beings. They both, separately and together, fought to restore the power of the ancient words and to speak modern ones with wholeness and genuineness. Despite the barriers in their own lives—Buber’e early disappointment, Rosenzweig’s struggle with german idealism and later with a terrible paralysis that left him unable to speak—they each came to see dialogue as a central fact of interhuman and human-divine relations.

[Fox then speaks of the time since 1933 when human language was debased and trivialized –Stalin, Hitler speeches; Orwellian visions; Vietnam war jargon, TV and advertisement babble.]

Yet Buber and Rosenzweig knew that language lives only in the mouths of speakers, human beings who face each other and who at every moment of conversation and contact literally translate for one another. The reading of the Bible is hopefully a cultural means for reawakening that conversation, for in the struggle to understand and apply these texts, one may come to perceive the importance of real words. A Bible translation should be the occasion for reaffirming the human desire to speak and be heard, for encouraging people to view their lives as a series of statements and responses—conversations, really. In sending the reader back to the text, the Buber-Rosenzweig Bible sought to counter the deadness of contemporary language and contemporary living which were all too apparent at the turn of the century, even before war and genocide began to take their toll. As we approach the end of that century [20th century], the same problems remain, altered further by the present revolution in communications. Amid the overcrowded air of cyberspace, the Hebrew Bible may still come to tell us that we do not live by bread alone, and that careful and loving attention to ancient words may help us to form the modern ones that we need.

Everett Fox

Clark University

Worcester, Massachusetts

January 1995/Shevat 5755