[The last installment for Chapter 3 of Rabbi Jonathan Sacks’ book—a most interesting read, that’s why I bother to type its long chapters. If you haven’t done so yet, please secure a copy of his book; downloadable on kindle from amazon.com. Also, if you haven’t done so yet, read the previous posts leading to this one. We will feature only one more chapter —the concluding one; what else is written between the beginning and the end, you have to find out for yourself when you buy your copy of the book. Reformatted for this post, image added.—Admin1.]

————————

The third story is simply told. We still do not know what it was about the seventeenth century that led to the rise of experimental science. Some claim it was religion: Protestantism in general or Calvinism in particular. Others claim it was the waning of religion. Some say it was an attempt to repair the Fall of man, who had been exiled from eden for wrongly eating of the tree of knowledge. Some say it was the attempt to build an Earthly paradise by the use of purely secular reason. Stephen Toulmin has argued, convincingly in my view, that it was the impact of the wars of religion of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that led figures like Descartes and Newton to seek certainty on the basis of a structure of knowledge that did not rest on dogmatic foundations.

One way or another, first science, then philosophy, declared their independence from theology and the great arch stretching from Jerusalem to Athens began to crumble.

- First came the seventeenth-century realisation that the Earth was not the centre of the universe.

- Then came the development of a mechanistic science that sought explanations in terms of prior causes, not ultimate purposes.

Then came the eighteenth-century philosophical assault, by Hume and Kant, on the philosophical arguments for the existence of God. Hume pointed up the weakness of the argument from design. Kant refuted the ontological argument.

- Then came the nineteenth century and Darwin. This was, on the face of it, the most crushing blow of all, because it seemed to show that the entire emergence of life was the result of a process that was blind.

We think of these as shaking the religious worldview of the Bible, but in fact they were something else entirely.

- For it was the Greeks who saw the Earth as the centre of the celestial spheres.

- It was Aristotle who saw purposes as causes.

- It was Cicero who formulated the argument from design.

- It was the Athenian philosophers who believed that there are philosophical proofs for the existence of God.

The Hebrew Bible never thought in these terms. The heavens proclaim the glory of God; they do not prove the existence of God. All that breathes praises its Creator; it does not furnish philosophical verification of a Creator. In the Bible, people talk to God, not about God. The Hebrew word da’at, usually translated as ‘knowledge’, does not mean knowledge at all in the Greek sense, as a form of cognition. It means intimacy, relationship, the touch of soul and soul. God, for the Bible, is not to be found in nature for God transcends nature, as do we whenever we exercise our freedom. In Hebrew the word for universe, olam, is semantically related to the word ‘hidden’, ne’elam. God is present in nature but in a hidden way.

So the shaking of the foundations that took place between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries was, in reality, the undermining and eclipse of Greek rationalist tradition, not of the Judaic basis of faith itself, which, while respecting and honouring science as a form of divine wisdom, never allied itself to one particular scientific tradition and specifically distanced itself from certain aspects of Greek culture.

That means that the original basis of Abrahamic monotheism remains, whatever the state of science. For religious knowledge as understood by the Hebrew Bible is not to be construed as the model of philosophy and science, both left-brain activities. God is to be found in relationship, and in the meanings we construct when, out of our experience of the presence of God in our lives, we create bonds of loyalty and mutual responsibility known as covenants. People have sought in the religious life the kind of certainty that belongs to philosophy and science. But it is not to be found. Between God and man there is moral loyalty, not scientific certainty.

Construe knowledge on the basis of science and, with the best will in the world, you will discover at best only one aspect of God, the aspect the Hebrew Bible calls Elokim, the impersonal God of creation as opposed to the personal God of revelation.

This is Spinoza’s and Einstein’s God, and they were indeed two profoundly religious individuals — Novalis called Spinoza a ‘God-intoxicated man’. They could see God in the universe, and find awe at the universe’s complexity and law-governed order. What they could not conceive was God as the consecration of the personal, the Divinity that underwrites our humanity.

Elokim, the God of creation whose signature we can read in the natural world, is common ground between the God of Aristotle and the God of Abraham. These two great conceptions came together for almost seventeen centuries in Christianity and for a short period between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries in Islam (Averroes) and Judaism (Maimonides). But since the seventeenth century science and religion have gone their separate ways and the old synthesis no longer seems to hold.

But most of the Bible is about another face of God, the one turned to us in love, known in the Bible by the four-letter name that, because of its holiness, Jews call Hashem, the name’. This aspect of God is found in relationship, in the face of the human other that carries the trace of the divine Other. We should look for the divine presence in compassion, generosity, kindness, understanding, forgiveness, the opening of soul to soul. We create space for God by feeding the hungry, healing the sick, housing the homeless and fighting for justice. God lives in the right atmosphere of the brain, in empathy and interpersonal understanding, in relationships etched with the charisma of grace, not subject and object, command and control, dominance and submission.

Faith is a relationship in which we become God’s partners in the work of love. The phrase sounds absurd. How can an omniscient, omnipotent God need a partner? There is, surely, nothing he cannot do on his own. But this is a left-brain question. The right-brain answer is that there is one thing God cannot do on his own, namely have a relationship. God on his own cannot live within the free human heart. Faith is a relationship of intersubjectivity, the meeting point of our subjectivity with the subjectivity, the inwardness, of God. God is the personal reality of otherness. Religion is the redemption of solitude.

Faith is not a form of ‘knowing’ in the sense in which that word is used in science and philosophy. It is, in the Bible, a mode of listening. The supreme expression of Jewish faith, usually translated as ‘Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is one’ (Deuteronomy 6:4), really means ‘Listen, O Israel’. Listening is an existential act of encounter, a way of hearing the person beneath the words, the music beneath the noise. Freud, who disliked religion and abandoned his Judaism, was nonetheless Jewish enough to invent, in psychoanalysis, the ‘listening cure’; listening as the healing of the soul.

It may be that we are already embarked on a fourth story. Again, for me it began with an episode in Cambridge. I had been taking part in a debate on religion and science. this was just before the appearance of the string of books by the new atheists, and at the time I thought the subject was so passé that I assumed only a handful of people would turn up. To my surprise I discovered that the organisers had taken the largest auditorium in the university and it was filled to overflowing.

My opponent, the professor of the history of science, the late Peter Lipton, was generous and broad-minded. we found ourselves agreeing on almost everything — so much so the chair of proceedings, Lord Robert Winston, Britain’s most famous television scientist and a deeply religious Jew, said after about half an ahour, ‘In that case, I’m going to disagree with both of you.’ It was a good-natured and open conversation and left most of us feeling that religion and science, far from being opposed, were on the same side of the table, using their distinctive methods to help us better understand humanity, nature and our place in the scheme of things.

As we were leaving, a stranger came up to me, gentle and unassuming, and said, ‘I’ve just written a book that I think you might find interesting. If I may, I’ll send it to you.’ I thanked him and some days later the book arrived. It was called Just Six Numbers, and with a shock of recognition I realised who the stranger was; Sir Martin, now Lord, Rees, Astronomer Royal, Master of Trinity College, Cambridge and President of the Royal Society, the world’s oldest and most famous scientific association. Sir Martin was, in other words, Britain’s most distinguished scientist.

The thesis of the book was that there are six mathematical constants that determine the physical shape of the universe. Had any one of them been even slightly different, the unvierse as we know it would not exist. Nor would life. It was my first glimpse into the new cosmology and the string of recent discoveries of how improbably our existence actually is. James Le Fanu, in his 2009 book Why Us?, adds to this a slew of new findings in neuroscience and genetics to suggest that we are on the brink of a paradigm shift that will overturn the scientific materialism of the past two centuries:

The new paradigm must also lead to a renewed interest in and sympathy for religion in its broadest sense, as a means of expressing wonder at the ‘mysterium tremendum et fascinans’ of the natural world. It is not the least of the ironies of the New Genetics and the Decade of the Brain that they have vindicated the two main impetuses to religious belief — the non-material reality of the human soul and the beauty and diversity of the living world — while confounding the principle tenets of materialism: that Darwin’s ‘reason for everything’ explains the natural world and our origins, and that life can be ‘reduced’ to the chemical genes, the mind to the physical brain.

There may be, in other words, a new synthesis in the making. It will be very unlike the Greek-thought-world of the medieval scholastics with its emphasis on changelessness and harmony. Instead it will speak about the emergence of order, the distribution of intelligence and information processing, the nature of self-organising complexity, the way individuals display a collective intelligence that is a property of groups, not just the individuals that comprise them, the dynamic of evolving systems and what leads some to equilibrium, others to chaos. Out of this will emerge new metaphors of nature and humanity, flourishing and completeness. Right-brain thinking may reappear, even in the world of science, after its eclipse since the seventeenth century. Right and left may be closer alignment than they have been. I say more on the new science in chapters 11 and 14.

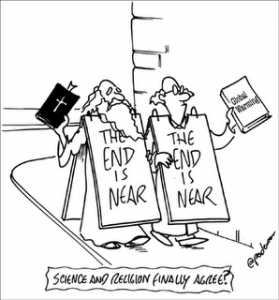

What I have sought to show in this chapter, however, is that there is a significant history in the Western experience of God and religion on the one hand, philosophy and science on the other. They came together in the grand, unique synthesis of Christianity from Paul, through the Church Fathers and the scholastics, to the seventeenth century. Since then they have been progressively separated, but they may be coming together again in ways we cannot forsee. There always was, though, an alternative, the road less travelled, adhered to by a tiny people the Jews.

On this view, religion, faith and God are not among the truths discovered by science or philosophy in the Greek and Western mode. They are about meaning. Meaning is made and sustained in conversations. It lives in relationships: in marriages, families, communities and societies. It is told in narrative, invoked in prayer, enacted in ritual, encoded in sacred texts, celebrated on holy days and sung in songs of praise.

The left brain, with its linear, atomising and generalising powers, is effective in dealing with things. It is not best in dealing with people. It does not understand the inner life of people, their hopes and fears, their aspirations and anxieties. Religion consecrates our humanity. In discovering God, singular and alone, our ancestors discovered the human individual, singular and alone. For the first time in history sanctity was conferred on the human individual as such, regardless of class, caste, colour or creed, as God’s image and likeness, God’s beloved.

Science takes things apart to see how they work. Religion puts things together to see what they mean. They speak different languages and use different powers of the brain. We sometimes fail to see this because of the way the religion of Abraham entered the mainstream consciousness of the West, not in its own language but in the language of the culture that gave birth to science. Once we recognise their difference we can move on, no longer thinking science and religion as friends who became enemies, but as our unique, bicameral, twin perspective on the difference between things and people, objects and subjects, enabling us to create within a world of blind forces a home for a humanity that is neither blind nor deaf to the beauty of the other as the living trace of the living God.

Reader Comments