Image from www.picstopin.com

[This was first posted September 3, 2012 as “Esau, who is Edom”; it is now updated with three commentaries added to the Sinaite’s perspective which is discussed first, as an introduction.

When we first started re-reading the Torah books, we thought it best to read without outside aid, just to test if today’s readers can follow the patriarchal narratives despite lack of knowledge about their cultural and historical context.

Our findings? Stories are stories, the easiest way to communicate teachings and lessons is to imbed these in the life choices and consequences of protagonists from whom we learn much because their life stories are memorable. We found ourselves emphathizing unexpectedly with figures who have been presented almost as ‘villains’ simply because they were not in the chosen line leading to the chosen people. Such is Esau with whom, if you haven’t noticed yet, we have sympathized with from the very start.

To this updated post, we now add commantaries from: Pentateuch and Haftorahs, ed. Dr. J.H. Hertz, RA/Robert Alter, and EF/Everett Fox whose translation The Five Books of Moses is featured in this website. This translation is downloadable, just google “Shocken Bible”.—Admin1.]

———————————

Why does the book of beginnings record so many genealogies, even of people groups on the periphery of the lineage of the chosen people?

- For one, to establish lines of descendants who would develop into nations that will figure as friend or foe to the Israelites in the 6 millennia long history of this enduring people of the Book.

- For another, it adds to the evidence proving the veracity of the stories recorded in the Hebrew Scriptures.

If you were to write a fictitious historical narrative, why bore your readers with one genealogy after another which would discourage them from reading further? But if you were to write a history of the beginnings of nations of the world, genealogies are necessary particularly in tracing back to the forbears of non-Israelites who became part of Israel, just like Caleb, son of Jephunneh the Kennizite.

Like other gentiles who read the Hebrew Scriptures, who worship the God who revealed Himself in those Scriptures, we take interest in the role that gentiles have played in the formation of the chosen people, in their interaction whether as kin, enemy or proselyte, to seek out samples we can emulate.

Esau the twin who turns out to be a good brother to Jacob is given a whole chapter for his progeny. To us he is admirable but not surprisingly, Jewish commentary do not paint a favorable picture because from him descended a people, the Edomites who became enemies to Jacob’s descendants:

- [www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/History/Edomites.html]-

Traditional enemies of the Israelites, the Edomites were the descendants of Esau who often battled the Jewish nation. Edom was in southeast Palestine, stretched from the Red Sea at Elath to the Dead Sea, and encompassed some of Israel’s most fertile land. The Edomites attacked Israel under Saul’s rulership.King David would later defeat the rogue nation, annexing their land. At the fall of the First Temple, the Edomites attacked Judah and looted the Temple, accelerating its destruction. The Edomites were later forcibly converted into Judaism by John Hyrcanus, and then became an active part of the Jewish people. Famous Edomites include Herod. who built the Second Temple.

- Rabbinic commentary is worse, we include it here only to show why we agree with and are closer to the Karaites in our reading of Scripture: [from ArtScroll notes on the struggle of Jacob with the mysterious “man”]

This confrontation was a cosmic event in Jewish history. The Rabbis explained that this “man” was the guardian angel of Esau (Rashi) in human guise. The Sages teach that every nation has an angel that guides its destiny as an “intermediary” between it and God. Two nations, however, are unique: Israel is God’s own people and just as Esau epitomizes evil, so his angel is the prime spiritual force of evil —Satan himself. Thus, this battle has the eternal struggle between good and evil, between man’s capacity to perfect himself and Satan’s determination to destroy him spiritually.

NSB@S6K

———————–

Genesis/Bereshith 36

[EF] Esav’s Descendants: The complicated genealogies and dynasties of this chapter close out the first part of the Yaakov cycle, strictly speaking. Fitting in the context of a society which lay great store by kinship and thus by careful remembering of family names, it may also indicate the greatness of Yitzhak’s line, as Chap. 25 had earlier done for Avraham. Certainly the lists give evidence of a time when the Edomites were more than merely Israel’s neighbors, assuming great importance in historical recollection (Speiser).

[RA] Chapter 36 offers the last of the major genealogies in Genesis. These lists of generations (toledot) and of kings obviously exerted an intrinsic fascination for the ancient audience and served as a way of accounting for historical and political configurations, which were conceived through a metaphor of biological propagation. (in fact, virtually the only evidence we have about the Edomite settlement is the material in this chapter.) As a unit in the literary structure of Genesis, the genealogies here are the marker of the end of a long narrative unit. What follows is the story of Joseph, a continuous sequence that is the last large literary unit of Genesis. The role of Esau’s genealogy is clearly analogous to that of Ishmael’s genealogy in chapter 25: before the narrative goes on to pursue the national line of Israel, an account is rendered of the posterity of the patriarch’s son who is not the bearer of the covenantal promise. But Isaac had given Esau, too, a blessing, however qualified, and these lists demonstrate the implementation of that blessing in Esau’s posterity.

The chapter also serves to shore up the narrative geographically, to the east, before turning tis attention to the south. Apart from the brief report in chapter 12 of Abraham’s sojourn in Egypt, which is meant to foreshadow the end of Genesis and the beginning of Exodus, the significant movement beyond the borders of Canaan has all been eastward, across the Jordan to Mesopotamia and back again. Esau now makes his permanent move from Canaan to Edom—the mountainous region east of Canaan, south of the Dead Sea and stretching down toward the Gulf of Aqabah. Once this report is finished, our attention will be turned first to Canaan and then to Egypt.

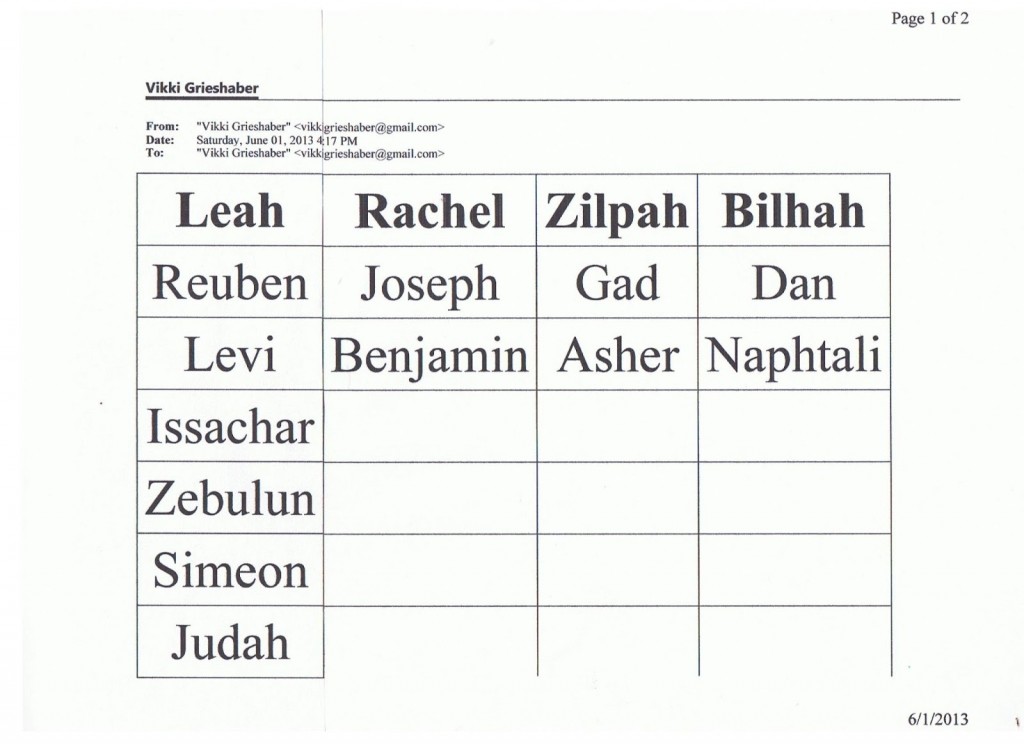

[RA] 1-8. This is the first of six different lists—perhaps drawn from different archival sources by the editor—that make up the chapter. Though it does record Esau’s sons, the stress is on his wives. These are both overlap and inconsistency among the different lists. These need not detain us here. The best account of these sundry traditions, complete with charts, is the discussion of this chapter in the Hebrew Encyclopedia ‘Olam haTanakh, though Nahum Sarna provides a briefer but helpful exposition of the lists in his commentary.

1 And these are the begettings of Esav—that is Edom. 2 Esav took his wives from the women of Canaan: Ada, daughter of Elon the Hittite, and Oholivama, daughter

[RA] Anah son of Zibeon. The Masoretic Text has “daughter of,” but Anah is clearly a man (cf. verse 24), and several ancient versions read “son.”

3 of Ana (and) granddaughter of Tziv’on the Hivvite,/ and Ba’semat, daughter of Yishmael and sister of Nevayot.4 Ada bore Elifaz to Esav, Ba’semat bore Re’uel,

5 Oholivama bore Ye’ush, Ya’lam, and Korah. These are Esav’s sons, who were born to him in the land of Canaan. 6 Esav took his wives, his sons and his daughters, and all the persons in his household, as well as his acquired-livestock, all his animals, and all his acquisitions that he had gained in the land of Canaan, and went to (another) land, away from Yaakov his brother;

[RA] another land. The translation follows the explanation gloss of the ancient Targums. The received text has only “a land.”

away from. Or, “because of.”

7 for their property was too much for them to settle together, the land of their sojourning could not support them, on account of their acquired-livestock.[EF] for their property was too much: Again recalling Avraham, in his conflict with Lot (13:6).

[RA] the land . . . could not support them. The language of the entire passage is reminiscent of the separation between Lot and Abraham in chapter 13. It is noteworthy that Esau, in keeping with his loss of birthright and blessing, concedes Canaan to his brother and moves his people to the southeast.

8 So Esav settled in the hill-country of Se’ir-Esav, that is Edom.

[RA] 9-14. The second unit is a genealogical list focusing on sons rather than wives.

9 And these are the begettings of Esav, the tribal-father of Edom, in the hill-country of Se’ir:10 These are the names of the sons of Esav: Elifaz son of Ada, Esav’s wife, Re’uel, son of Ba’semat, Esav’s wife. 11 The sons of Elifaz were Teiman, Omar, Tzefo, Ga’tam, and Kenaz.

12 Now Timna was concubine to Elifaz son of Esav, and she bore Amalek to Elifaz. These are the sons of Ada, Esav’s wife.

[RA] Timna . . . a concubine … bore…Amalek. If Amalek is subtracted, we have a list of twelve tribes, as with Israel and Ishmael. Perhaps the birth by a concubine is meant to set Amalek apart, in a status of lesser legitimacy. Amalek becomes the hereditary enemy of Israel, whereas the other Edomites had normal dealings with their neighbors to the west.

13 And these are the sons of Re’uel: Nahat and Zerah, Shamma and Mizza. These were the sons of Ba’semat, Esav’s wife.14 And these were the sons of Oholivama, daughter of Ana, (and) granddaughter of Tziv’on (and) Esav’s wife: She bore Ye’ush and Ya’lam and Korah to Esav.

[EF] Tzi’von: The name means “hyena.” Such animal names have long been popular in the region and occur a number of times in this chapter (Vawter).

[RA] 15-19. The third unit is a list of chieftains descended from Esau.

15 These are the families of Esav’s sons: From the sons of Elifaz, Esav’s firstborn, are: the Family Teiman, the Family Omar, the Family Tzefo, the Family

[EF] families: Others use “chieftains.”

[RA] chieftains. It has been proposed that the Hebrew aluf means “clan,” but that seems questionable because most of the occurrences of the term elsewhere in the Bible clearly indicate a person, not a group. The difficulty is obviated if we assume that an ‘aluf is the head of an ‘elef, a clan. The one problem with this construction, the fact that in verses 40 and 41 ‘aluf is joined with a feminine proper noun, may be resolved by seeing a construct form there (“chieftain of Timna” isntead of “chieftainTimna”).

16 Kenaz,/ the Family Korah, the Family Ga’tam, the Family Amalek; these are the families from Elifaz in the land of Edom, these are the sons of Ada.17 And these are the Children of Re’uel, Esav’s son: the Family Nahat, the Family Zerah, the

Family Shamma, the Family Mizza; these are the families from Re’uel in the land of Edom, these the Children of Ba’semat, Esav’s wife.

18 And these are the Children of Oholivama, Esav’s wife: the Family Ye’ush, the Family Ya’lam, the Family Korah; these are the families from Oholivama, daughter of Ana, Esav’s wife.

19 These are the Children of Esav and these are their families.— That is Edom.

[RA] 20-30. The fourth unit of the chapter is a list of Horite inhabitants of Edom. The Horites—evidently the term was used interchangeably with Hittite—were most probably the Hurrians, a people who penetrated into this area from Armenia sometime in the first half of the second millennium B.C.E. They seem to have largely assimilated into the local population, a process reflected in the fact that, like everyone else in these lists, they have West Semitic names.

20 These are the sons of Se’ir the Horite, the settled-folk of the land:

[RA] who had settled in the land. “Settlers [or inhabitants’ of the land” is closer to the Hebrew. That is, the “Horites” were the indigenous population by the time the Edomites invaded from the west, during the thirteenth century B.C.E.

21 Lotan and Shoval and Tziv’on and Ana and Dishon and Etzer and Dishan. These are the Horite families, the Children of Se’ir in the land of Edom.22 The sons of Lotan were Hori and Hemam, and Lotan’s sister was Timna.

23 And these are the sons of Shoval: Alvan and Manahat and Eval, Shefo and Onam.

24 And these are the sons of Tziv’on: Ayya and Ana. —That is the Ana who found the yemim in

the wilderness, as he was tending the donkeys of Tziv’on his father.

[EF] yemim: Hebrew obscure; some use “hot springs,” “lakes.”

[RA] Aiah. The Masoretic Text reads “and Aiah.”

who found the water in the wilderness. The object of the verb in the Hebrew, yemim, is an anomalous term, and venerable traditions that render it as “mules” or “hot springs” have no philological basis. This translation follows E.A. Speiser’s plausible suggestion that a simple transposition of the first and second consonants of the word occurred and that the original reading was mayim, “water.” Discovery of any water source in the wilderness would be enough to make it noteworthy for posterity.

25 And these are the sons of Ana: Dishon-and Oholivama was Ana’s daughter.26 And these are the sons of Dishon: Hemdan and Eshban and Yitran and Ceran.

[EF] Dishon: The traditional text uses “Dishan”, but look at I Chron. 1;41.

[RA] Dishon. The Masoretic Text reads “Dishan,” who is his brother, and whose offspring are recorded two verses later. There is support for “Dishon” in some of the ancient versions.

27 These are the sons of Etzer: Bilhan and Zaavan and Akan.28 These are the sons of Dishan: Utz and Aran.

29 These are the Horite families: the Family Lotan, the Family 30 Shoval, the Family Tziv’on, the Family Ana,/ the Family Dishon, the Family Etzer, the

Family Dishan. These are the families of the Horites, according to their families in the land of Se’ir.

[RA] by their clans. The translation revocalizes the Masoretic ‘alufeyhem as ‘alfeyhem (the consonants remain identical) to yield “clans.”

31-39. The fifth unit of the chapter is a list of the kings of Edom. They do not constitute a dynasty because none of the successors to the throne is a son of his predecessor.

31 Now these are the kings who served as king in the land of Edom, before any king of the Children of Israel served as king:

[RA] before any king reigned over the Israelites. The phrase refers to the establishment of the monarchy beginning with Saul and not, as some have proposed, to the imposition of Israelite suzerainty over Edom by David, because of the particle Ie (“to,” “for,” “over”), rather than mi (“from”) prefixed to the Hebrew for “Israelites.” This is one of those brief moments when the later perspective in time of the writer pushes to the surface in the Patriarchal narrative.

32 In Edom, Bela son of Be’or was king; the name of his city was Dinhava.33 When Bela died, Yovav son of Zerah of Botzra became king in his stead.

34 When Yovav died, Husham from the land of the Teimanites became king in his stead.

35 When Husham died, Hadad son of Bedad became king in his stead-who struck Midyan in the territory of Mo’av, and the name of his city was Avit.

36 When Hadad died, Samla of Masreka became king in his stead.

37 When Samla died, Sha’ul of Rehovot-by-the-river became king in his stead.

[RA] Rehoboth-on-the-River. Rehoboth means “broad places”: in urban contexts, in the singular, it designates the city square; here it might mean something like “meadows.” Rehoboth-on-the-River is probably meant to distinguish this palce from some other Rehoboth, differently situated.

38 When Sha’ul died, Baal-hanan son of Akhbor became king in his stead.39 When Baal-Hanan son of Akhbor died, Hadar became king in his stead; the name of his city was Pa’u, and the name of his wife, Mehetavel daughter of Matred, daughter of Mei-zahav.

[RA] Hadad. The Masoretic Text has “Hadar,” but this is almost certainly a mistake for the well-attested name Hadad, as Chronicles, and some ancient versions and manuscripts, read. In Hebrew, there is only a small difference between the graphemes for r and for d.

40-43. The sixth and concluding list of the collection is another record of the chieftains descended from Esau. Most of the names are different, and the list may reflect a collation of archival materials stemming from disparate sources. This sort of stitching together of different testimonies would be in keeping with ancient editorial practices.

40 Now these are the names of the families from Esav, according to their clans, according to their local-places, by their names:41 The Family Timna, the Family Alvan, the Family Yetet,/ the Family Oholivama, the Family Ela, the Family

42 Pinon,/ the Family Kenaz, the Family Teiman, the Family

43 Mivtzar,/ the Family Magdiel, the Family Iram. These are the families of Edom according to their settlements in the land of their holdings. That is Esav, the tribal-father of Edom.