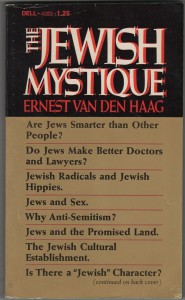

Image from amazon.com

[First posted in 2013. This is part of the series The Bible as ‘Literature’ from the excellent MUST READ/MUST OWN:

The Literary Guide to the Bible,

eds. Robert Alter & Frank Kermode.

Imagine! Note: Robert Alter is the translator of THE FIVE BOOKS OF MOSES, our alternate translation together with Everett Fox’s THE FIVE BOOKS OF MOSES. We highly recommend these translations of the TORAH as MUST OWN!

Hebrew writers of antiquity already had a grasp of the poetic forms and expressions which best expressed the language of Divinity in their Scriptures and yet western scholars had for so long ignored the value of understanding biblical language as ‘literature’. Serious students of the Bible stand to gain from taking a break from ‘religious orientation’ and learn how to read The Hebrew Scriptures (not the Old Testament) through the lens of professors/teachers of Literature. Please check out related posts:

This book is downloadable on a kindle app from amazon.com. Reformatting and highlights added–Admin1.]

————————–

The Characteristics of Ancient Hebrew Poetry

Robert Alter

Exactly what is the poetry of the Bible,

and what role does it play

in giving form to the biblical religious vision?

The second of these two questions obviously involves all sorts of imponderables. One would think that, by contrast, the first question should have a straightforward answer; but in fact there has been considerable confusion through the ages about—

- where there is poetry in the Bible

- about the principles on which that poetry works.

To begin with, biblical poetry occurs almost exclusively in the Hebrew Bible.

There are, of course, grandly poetic passages in the New Testament—perhaps most impressively in the Apocalypse—but only the Magnificat of Luke 1 is fashioned as formal verse.

Readers of the Old Testament often cannot easily see where the poetry is supposed to be because in the King James Version, which has been the text used by most English-speaking people, nothing is laid out as lines of verse. This confusing typographic procedure is in turn faithful to the Hebrew manuscript tradition, which runs everything together in dense, unpunctuated columns. (There are just a few exceptions where there is a spacing out roughly corresponding to lines of verse, as in the Song of the Sea, Exod. 15; Moses’ valedictory song, Deut. 32; and an occasional manuscript of Psalms.)

What has accompanied this graphic leveling of poetry with prose in the text is a kind of cultural amnesia about biblical poetics.

- Over the centuries, Psalms was most clearly perceived as poetry, probably because of the actual musical indications in the texts and the obvious liturgical function of many of the poems.

- The status as poetry of the Song of Songs and Job was, because of the lyric beauty of the one and the grandeur of the other, also generally kept in sight, however farfetched the notions about the formal character of the verse in these books.

- Proverbs was somewhat more intermittently seen as poetry, and it was often not understood that the Prophets cast the larger part of their message in verse.

- Finally, it is only in our century that scholars have begun to realize to what extent the prose narratives of the Bible are studded with brief verse insets, usually introduced at dramatically justified or otherwise significant junctures in the stories.

Over the last two millennia—and, for many, down to the present—being a reader of biblical poetry has been like being a reader of Dryden and Pope who comes from a culture with no concept of rhyme: you would loosely grasp that the language was intricately organized as verse, but with the uneasy feeling that you were somehow missing something essential you couldn’t quite define.

The central informing convention of biblical verse was rediscovered in the mid-eighteenth century by a scholarly Anglican bishop, Robert Lowth. He proposed that lines of biblical verse comprised two or three “members” (which I shall call “versets”) parallel to each other in meaning. Like many a good discovery, Bishop Lowth’s perception has not fared as well as it might. The realization soon dawned that some of what he called parallelism was not semantically parallel at all. This recognition led to a sometimes confusing proliferation of subcategories of parallelism and, in our own time, to various baby-with-bath water operations in which syllable count, units of syntax, or some other formal feature was proposed as the basis for biblical poetry, parallelism being relegated to a secondary or incidental position.

In another direction, at least one scholar, despairing of a coherent account of biblical verse, has contended that there was no distinct concept of formal versification in ancient Israel but merely a “continuum” of parallelistic rhetoric from prose to what we misleadingly call poetry. Some of these confusions can be sorted out, and as a result we may be able to see more clearly the distinctive strength and beauty of the biblical poems, for an understanding of the poetic system is always a precondition to reading the poem well.

Semantic parallelism, though by no means invariably present, is a prevalent feature of biblical verse.

That is, if the poet says “hearken” in the first verset, he is likely to say something like “listen” or “heed” in the second verset. This parallelism of meaning, which is often joined with a balancing of the number of rhythmic stresses between the versets and sometimes by parallel syntactic patterns as well, seems to have played a role roughly analogous to that of iambic pentameter in Shakespeare’s dramatic verse: it is an underlying formal model which the poet feels free to modify or occasionally to abandon altogether.

In longer biblical poems, a departure from parallelism is sometimes used to mark the end of a distinct; elsewhere parallelism is occasionally set aside in favor of a small-scale narrative sequence within the line; and few poets appear simply to have been less fond than others of the symmetries of parallelism.

Before attempting to sharpen this rather general concept of poetic parallelism, let me offer some brief examples of its basic patterns of development.

David’s victory psalm (2Sam. 22) presents a nice variety of possibilities because it is relatively long for a biblical poem and it includes quasi-narrative elements and discrete segments with formally marked transitions. In the fifty-three lines of verse that constitute the poem, few approach a perfect coordinated parallelism not only for meaning but also of syntax and rhythmic stresses. Thus: “For with you I charge a barrier, /with my God I vault a wall” (v.30). Here each semantically parallel term in the two versets is in the same syntactic position: with you/with my God, I charge / vault, a barrier / a wall. Though our knowledge of the phonetics of the biblical Hebrew involves a certain margin of conjecture, the line with its system of stresses, as vocalized in the Masoretic Hebrew text, would sound something like this: ki bekha ‘aruts gedud/ be’ lohai adaleg-shur, yielding a 3 + 3 parallelism of stressed syllables, which in fact is the most common pattern in biblical verse. (The rule is that there are never less than two stresses in a verset and never more than four, and no two stresses follow each other without an intervening unstressed syllable; and there are often asymmetrical combinations of 4 + 3 + or 3 + 2.)

It is hardly surprising that biblical poets should very often seek to avoid such regularity as we have just seen, through different kinds of elegant—and sometimes significant—variation. Often, syntactically disparate clauses are used to convey a parallelism of meaning, as in verse 29: “For you are my lamp, O Lord, / the Lord lights up my darkness,” where the second-person predicative assertion that the Lord is a lamp is transformed into a third-person narrative statement in which the Lord now governs a verb of illumination. Even when the syntax of the two versets is much closer than this, variations may be introduced, as in two lines from the beginning of the poem (vv.5-6) that describe the speaker having been on the brink of death. I will reproduce the precise word order of the Hebrew, though at a cost of awkwardness, for biblical Hebrew usage is much more flexible than modern English as to subject-predicate order.

For there encompassed me the breakers of death,

The rivers of destruction terrified me.

The cords of Sheol surrounded me,

there greeted me the snares of death.

The syntactic shape of these two lines, which preserve a regular semantic parallelism through all four versets as well as a 3-3 stress in both lines, is a double chiasm:

(1) encompassed-breakers-rivers-terrified;

(2) cords-surrounded-greeted-snares.

In the first line the verbs of surrounding are the outside terms, the entrapping agencies of death, the inside terms of the chiasm (abba); and in the second line this order is reversed (baab). This maneuver, which, like the interlinear parallelism, is quite common in biblical verse, may be nothing more than elegant variation to avoid mechanical repetitiousness, though one suspects here that the chiastic boxing in and reversal of terms help reinforce the feeling of entrapment that is being expressed: as the two lines unfold, the reader can scarcely choose between a sense of being multifariously surrounded and a sense of the multiplicity of the instruments of death.

Another frequent pattern for bracketing the two versets together involves an elliptical syntactic parallelism, usually through the introduction of a verb at the beginning of the first verset which does double duty for the second verset as well, as in verse 15: “He sent forth bolts and scattered them, / lighting, and overwhelmed them.” The ellipsis of “hesent-forth” (one word and one accented syllable in the Hebrew) produces a 3-2 stress pattern, which also involves a counterposing of three Hebrew words to two. (It should be said that biblical Hebrew is much more compact than any translation can suggest, with subject, object, possessive pronoun, preposition, and so forth indicated by suffix truncation of the second verset conveys a certain abruptness which the poet may have felt intuitively was appropriate for the violent action depicted. Elsewhere in biblical poetry, when ellipsis through a double-duty verb occurs while the parallelism of stresses between versets in maintained, the extra rhythmic unit in the second verset is used to develop semantic material introduced in the first verset.

Here is a characteristic instance from Moses’ valedictory song (Duet. 32:13): “He suckled him with honey from a rock, / and oil from a flinty stone.” That is, since the verb “he-suckled-him-with” (again a single word in the Hebrew) does double duty for the second verset, rhythmic space is freed in the second half of the line in which the poet can elaborate the simple general term “rock” into the complex term “flinty stone,” which is a particular instance of the general category, and one that brings out the quality of hardness. (The development of meaning within semantic parallelism is discussed in detail later.)

It is beyond my purposes here to classify all the subcategories of parallelism that present themselves in David’s victory psalm, but two additional cases are worth looking at to round out our provisional sense of the spectrum of possibilities. Verse 9, like the one that precedes it in 2 Samuel 22, is triadic: “Smoke came out of his nostrils, / fire from his mouth consumed, / coals glowed round him.”

First, let me comment briefly on the role of triadic lines in the biblical poetic system. Dyadic lines, as in all our previous examples, definitely predominate, but the poets have free recourse to triadic lines with none of the uneasy conscience manifested, say, by English Augustan poets when they introduce triplets into a poem composed in heroic couplets. In longer poems such as this, triadic lines can be used to mark the beginning or the end of a segment, as here the triadic verses 8-9 initiate the awesome seismic description of the Lord descending from on high to do battle with his foes. Elsewhere, triadic lines are simply interspersed with dyadic ones, and in some poems they are cultivated when the poet wants to express a sense of tension or instability, using the third verset to contrast or even reverse the first two parallel versets. Now, the smoke-fire-coals series quoted above involves approximately parallel concepts and actions, but the terms are also sequenced, temporally and logically, moving from smoke to its source to an incandescence so intense that everything around it is ignited. This progression, too, reflects a more general feature of poetic parallelism in the Bible to which we shall return.

Finally, biblical poetry abounds in lines like the one immediately following the line just quoted: “He tilted the heavens, came down, / deep mist beneath his feet” (v. 10). Here the only “parallelism” between the second verset and the first is one of rhythmic stresses (again 3-3). Otherwise, the second verset differs from the first in both syntax and meaning. The fairly frequent occurrence of such lines is no reason either to contort our definition of parallelism or to throw out the concept as a governing principle of Hebrew verse. The system, as I proposed before, is rather one in which semantic parallelism predominates without being regarded as an absolute necessity for every line. In this instance the poet seems to be pursuing a visual realization of the narrative momentum of the line (and, indeed, the momentum carries down through a whole sequence of lines); first he presents the Lord tilting the heavens and descending, and then, as the eye of the beholder plunges, a picture in the locative second clause of the deep mist beneath God’s feet as he descends. This yields a more striking effect than would a regular parallelism such as “He tilted the heavens, came down, / he plummeted to the earth,” and is a small but characteristic indication of the suppleness with which the general convention of parallelism is put to use by biblical poets.

Now, the greatest stumbling block in approaching biblical poetry has been the misconception that parallelism implies synonymity, saying the same thing twice in different words. I would argue that good poetry at all times is an intellectually robust activity to which such laziness is alien, that poets understand more subtly than linguists that there are no true synonyms, and that the ancient Hebrew poets are constantly advancing their meanings where the casual ear catches mere repetition.

Not surprisingly, some lines of biblical poetry approach a condition of equivalent statement between the versets more than others. Thus: “He preserves the paths of justice, / and the way of his faithful ones he guards” (Prov. 2:8). By my count, however, such instances of nearly synonymous restatement occur in less than a quarter of the lines of verse in the biblical corpus. The dominant pattern is a focusing, heightening, or specification of ideas, images, actions, themes from one verset to the next, If something is broken in the first verset, it is smashed or shattered in the second verset; if a city is destroyed in the first verset, it is turned into a heap of rubble in the second. A general term in the first half of the line is typically followed by a specific instance of the general category in the second half; or, again, a literal statement in the first verset becomes a metaphor or hyperbole in the second.

The notion that repetition in a text is very rarely simple restatement has long been understood by rhetoricians and literary theorists. Thus the Elizabethan rhetorician Hoskins—might the King James translators have read him?—acutely observes that “in speech there is no repetition without importance.” What this means to us as readers of biblical poetry is that instead of listening to an imagined drumbeat of repetitions, we need constantly to look for something new happening from one part of the line to the next.

The case of numbers in parallelism is especially instructive. If the underlying principle were really synonymity, we would expect to find, say, “forty” in one verset and “two score” in the other. In fact the almost invariable rule is an ascent on the numerical scale from first to second verset, either by one, or by a decimal multiple, or by a decimal multiple of the first number added to itself. And as with numbers, so with images and ideas; there is a steady amplification or intendification of the original terms. Here is a paradigmatic numerical instance: “How could one pursue a thousand, / and two put ten thousand to flight?” (Duet. 32:30).

An amusing illustration of scholarly misconception about what is involved poetically in such cases is a common contemporary view of the triumphal song chanted by the Israelite women: “Saul has smitten his thousands, / David, his tens of thousands” (1 Sam. 18:7). It has been suggested that Saul’s anger over these words reflects his paranoia, for he should have realized that in poetry it is a formulaic necessity to move from a thousand to ten thousand, and so the women really intended no slight to him. Such a suggestion assumes that somehow poetry conjures with formulaic devices indifferent to meaning. Saul may indeed have been paranoid, but he knew perfectly well how the Hebrew poetry of his era worked and understood that meanings were quite pointedly developed from one half of the line to the other. In fact the prose narrative in 1 Samuel 18 strongly confirms the rightness of Saul’s “reading,” for the people are clearly said to be extravagantly enamored of David as they are not of Saul.

Let me propose a few examples of this dynamic movement within the line, and then try to suggest something about the compelling religious and visionary ends that are served by this distinctive poetics. (For the sake of convenience, I have chosen almost all my examples from Psalms.) In the first group, the italics in the second versets indicate the point at which seeming repetition becomes a focusing, a heightening, a concretization of the original material:

- “Let me hear joy and gladness, / let the bones you have crushed exult” (Ps. 51:10);

- “How long, O Lord, will you be perpetually incensed, / like a flame your wrath will burn (Ps. 79:5);

- “He counts the number of the stars, / each one he calls by name” (Ps. 147:4).

These three lines illustrate a small spectrum of possibilities of semantic focusing between the two versets.

- In the first example, the general joy and gladness of the first verset become sharper through the constructive introduction of the crushed bones in the second verset, and bones exulting is, of course, a more vividly metaphorical restatement of the idea of rejoicing.

- In the second example, the possible hint of the notion of heat in the term for “incensed” (te’enaf, which might derive etymologically from the hot breath from the nostrils) becomes in the second verset a full-fledged metaphor of wrath burning like a flame.

- In the third example, there is no recourse to metaphor, but there is an obvious focusing in the “parallel” verbs of the two versets: calling something by name, which in biblical world implies intimate relation, knowledge of the essence of the thing, is a good deal more than mere counting. The logical structure of this line, which is quite typical of biblical poetics, would be something like this: not only can God count the innumerable stars (first verset) but he even knows the name of (or gives a name to) each single star.

Since the three examples we have just considered move from incipiently metaphorical to explicitly metaphorical to literal, a few brief observations may be in order about the role of figurative language in biblical poetics.

Striking imagery does not seem to have been especially valued for itself, as it would come to be in many varieties of European post-Romantic poetry. Some poets favor nonfigurative language, and very often, as we have seen, figures are introduced in the second verset as a convenient means among several possible ones for heightening some notion that appears in the first verset.

In any case, the biblical poets whole were inclined to draw on a body of more or less familiar images without consciously striving for originality of invention in their imagery.

- Wrath kindles, burns, consumes;

- protection is a canopy, a sheltering wing, shade in blistering heat;

- solace or renewal is dew, rain, streams of fresh water; and so forth.

The effectiveness of the image derives in part from its very familiarity, perhaps its archetypal character, in part from the way it is placed in context and, quite often, extended and intensified by elaboration through several lines or by reinforcement with related images. However, there is no overarching symbolic pattern, as some have claimed, in the images used by biblical poets, and there is no conventional limitation set on the semantic fields from which the images are drawn.

Though biblical poetry abounds in pastoral, agricultural, topographical, and meteorological images, the manufacturing processes of ancient Near Eastern urban culture are also frequently enlisted by the poets: the crafts of the weaver, the dryer, the launderer, the potter, the builder, the smith, and so forth. This freedom to draw images from all areas of experience, even in a poetic corpus largely committed to conventional figures, allows for some striking individual images.

The Job poet in particular excels in such invention, likening the swiftness of human existence to the movement of the shuttle on a loom, the fashioning of the child in the womb to the curdling of cheese, the mists over the waters of creation to swaddling cloths, and in general making his imagery a strong correlative of his extraordinary sense both of man’s creaturely contingency and of God’s overwhelming power.

As for the operation of poetic parallelism within the line, the possibilities of complication of meaning are too various to be discussed comprehensively here, but an important second category of development between versets deserves mention. In the following pair of line, the parallelism within the line is of a rather special kind, involving something other than intensification:

The teaching of his God is in his heart,

His footsteps will not stumble.

The wicked spies out the just,

and seeks to kill him. (Ps. 37:31-32)

In the first of these lines, the statements of the two versets do correspond to each other, but the essential nature of the correspondence is casual: if you keep the Lord’s teaching, you can count on avoiding calamity. In the next line, causation is allied with temporal sequence. That is, to try to kill someone is a more extreme act of malice than to lie in wait for him for him and hence n “intensification,” but the two are different points in a miniature narrative continuum: first the lying in wait, then the attempt to kill.

We see the same pattern in the following image of destruction, where the first verset presents the breaking down of fortress walls, the second verset the destruction of the fortress itself: “You burst through all his barriers, / you turned his strongholds to rubble” (Ps. 89:41).

It is sometimes asked what happened to narrative verse in ancient Israel, for whereas the principal narratives of most other ancient cultures are in poetry, narrative proper in the Hebrew Bible is almost exclusively reserved for prose.

One partial answer would be that the narrative impulse, which for a variety of reasons is withdrawn from the larger structure of the poem, often reappears on a more microscopic level, with the line, or in a brief sequence of lines, in the articulation of the poem’s imagery, as in the examples just cited. In quite a few instances this narrativity within the line is perfectly congruent with what I have described as the parallelism of intensification. Both elements are beautifully transparent in these two versets from Isaiah: “Like a pregnant woman whose time draws near, / she trembles, she screams in her birth pangs” (Isa. 26:17). The second verset, of course, not only is more concretely focused than the first but also represents a later moment in the same process—from very late pregnancy to the midst of labor.

This impulse of compact narrativity within the line is so common that it is often detectable even in the one-line poems that are introduced as dramatic heightening in the prose narratives. Thus, when Jacob sees Joseph’s bloodied tunic and concludes that his son has been killed, he follows the words of pained recognition, “It’s my son’s tunic “ with a line of verse that is a kind of miniature elegy: “An evil beast has devoured him, / torn, oh torn, is Joseph” (Gen. 37:33). The second verset is at once a focusing of the act of devouring and an incipiently narrative transition from the act to its awful consequence: a ravening beast has devoured him, and as the concrete result his body has been torn to shreds.

We see another variation of the underlying pattern in the line of quasi-prophetic (and quite mistaken) rebuke that the priest Eli pronounces to the distraught Hannah, whose lips have been moving in silent prayer: “How long will you be drunk? / Put away your wine!” (1 Sam. 1:14). Some analysts might be tempted to claim that both versets here, despite their semantic and syntactic dissimilarity, have the same “deep structure” because they both express outrage at Hannah’s supposed state of drunkenness, but I think we are in fact meant to read the line by noting differentiation. The first verset suggests that to continue in a state of inebriation in the sanctuary is intolerable; the second verset projects that attitude forward on a temporal axis (narrativity in the imperative mode) by drawing the consequence that the woman addressed must sober up at once.

Beyond the scale of the one-line poem, this element of narrativity between versets plays an important role in the development of meaning because so many biblical poems, even if they are not explicitly narrative, are concerned in one way or another with process. Psalm 102 is an intrusive case in point. The poem is a collective supplication on behalf of Israel in captivity. (Since it begins and ends in the first-person singular, it is conceivable that it is a reworking of an older individual supplication.) A good many lines exhibit the movement of intensification or focusing we observed earlier.

- Verse 3 is a good example: “For my days have gone up in smoke, / my bones are charred like a hearth.”

- Other lines reflect complementarily, such as verse 6: “I resembled the great owl of the desert, / I became like an owl among ruins.”

But because the speaker of the poem is, after all, trying to project a possibility of change out of the wasteland of exile in which he finds himself, a number of lines show a narrative progression from the first verset to the second because something is happening, and it is not just a static condition that is being reported.

Narrativity is felt particularly as God moves into action in history:

- “For the Lord has built up Zion, / he appears in his glory” (v. 16). That is, as a consequence of his momentous act of rebuilding the ruins of Zion (first verset), the glory of the Lord again becomes globally visible (second verset).

- Then the Lord looks down from heaven “to listen to the groans of the captive, / to free those condemned to death” (v. 20)—first the listening, then the act of liberation.

- God’s praise thus emanates from the rebuilt Jerusalem to which the exiles return “when nations gather together, / and kingdoms, to serve the Lord” (v. 22).

- Elsewhere in Psalms, the gathering together of nations and kingdoms may suggest a mustering of armies for attack on Israel, but the last phrase of the line, “to serve [or worship] the Lord,” functions as a climactic narrative revelation:

- this assembly of nations is to worship God in his mountain sanctuary, now splendidly reestablished.

In sum, the narrative momentum of these individual lines picks up a sense of historical process and helps align the collective supplication with the prophecies of return to Zion in Deutero-Isaiah, with which this poem is probably contemporaneous.

The last point may begin to suggest to the ordinary reader, who with good reason thinks of the Bible primarily as a corpus of religious writings, what all these considerations of formal poetics have to do with the urgent spiritual concerns of the ancient Hebrew poets. I don’t think there is ever a one-to-one correspondence between poetic systems and views of reality, but I would propose that a particular poetics may encourage or reinforce a particular orientation toward reality. For all the untold reams of commentary on the Bible, this remains a sadly neglected question.

One symptomatic case in point: a standard work on the basic forms of prophetic discourse by the German scholar Claus Westermann never once mentions the poetic vehicle used by the Prophets and makes no formal distinction between, say, a short prophetic statement in prose by Elijah and a complex poem by Isaiah. Any intrinsic connection between the kind of poetry the Prophets spoke and the nature of their message is simply never contemplated.

Biblical poetry, as I have tried to show, is characterized by an intensifying or narrative development within the line; and quite often this “horizontal” movement is then projected downward in a “vertical” focusing movement through a sequence of lines or even through a whole poem. What this means is that the poetry of the Bible is concerned above all with dynamic process moving toward some culmination.

The two most common structures, then, of biblical poetry are a movement of intensification of images, concepts, themes through a sequence of lines, and a narrative movement—which most often pertains to the development of metaphorical acts but can also refer to literal events, as in much prophetic poetry.

The account of the Creation in the first chapter of Genesis might serve as a model for the conception of reality that underlines most of this body of poetry: from day to day new elements are added in a continuous process that culminates in the seventh day, the primordial sabbath. It would require a close reading of whole poems to see fully how this model is variously manifested in the different genres of biblical poetry, but I can at least sketch out the ways in which the model is perceptible in verse addressed to personal, philosophical, and historical issues.

The poetry of Psalms has evinced an extraordinary power to speak to the lives of countless individual readers and has echoed through the work of writers as different as Augustine, George Herbert, Paul Claudel, and Dylan Thomas. Some of the power of the psalms may be attributed to their being such effective “devotions upon emergent occasions,” as John Donne, another poet strongly moved by these biblical poems, called a collection of his meditations.

The sense of emergency virtually defines the numerically predominant subgenre of psalm, the supplication. The typical—though of course not invariable—movement of the supplication is a rising line of intensity toward a climax of terror or desperation. The paradigmatic supplication would sound something like this: You have forgotten me, O Lord; you have hidden your face from me; you have thrown me to the mercies of my enemies; I totter on the brink of death, plunge into the darkness of the Pit. At this intolerable point of culmination, when there is nothing left for the speaker but the terrible contemplation of his own imminent extinction, a sharp reversal takes place. The speaker either prays to God to draw him out of the abyss or, in some poems, confidently asserts that God is in fact already working this wondrous rescue. It is clear why these poems have reverberated so strongly in the moments of crisis, spiritual or physical, of so many readers, and I would suggest that the distinctive capacity of biblical poetics to advance along a steeply inclined plane of mounting intensities does much to help the poets imaginatively realize both the experience of crisis and the dramatic reversal at the end.

Certainly there are other, less dynamic varieties of poetic structure represented in the biblical corpus, including the Book of Psalms. The general fondness of ancient Hebrew writers in all genres for so-called envelope structures (in which the conclusion somehow echoes terms or whole phrases from the beginning) leads in some poems to balanced, symmetrically enclosed forms, occasionally even to a division into parallel strophes, as in the Song of the Sea (Exod. 15).

The neatest paradigm for such symmetrical structures in Psalm 8, which, articulating a firm belief in the beautiful hierarchical perfection of creation, opens and closes with the refrain “Lord, our master, / how majestic is your name in all the earth!”

Symmetrical structures, because they tend to imply a confident sense of the possibility of encapsulating perception, are favored in particular by poets in the main line of Hebrew Wisdom literature—but not by the Job poet, who works in what has been described as the “radical wing” of biblical Wisdom writing. Thus the separate poems that constitute chapters 5 and 7 of Proverbs, though the former uses narrative elements and the latter is a freestanding narrative, equally employ neat envelope structures as frames to emphasize their didactic points.

The Hymn to Wisdom in Job 28, which most scholars consider to be an interpolation, stands out structure, being neatly divided into three symmetrical strophes marked by a refrain. Such instances, however, are no more than exceptions that prove the rule, for the structure that predominates in all genres of biblical poetry is one in which a kind of semantic pressure is one in which a kind of semantic pressure is built from verset to verset and line to line, finally reaching a climax or a climax and reversal.

This momentum of intensification is felt somewhat differently in the text that is in many respects the most astonishing poetic achievement in the biblical corpus, the Book of Job. Whereas the psalm-poets provided voices for the anguish and exultation of real people, Job is a fictional character, as the folktale stylization of the introductory prose narrative means to intimate.

In the rounds of debate with the three Friends, poetry spoken by fictional figures is used to ponder the enigma of arbitrary suffering that seems a constant element of the human condition. One of the ways in which we are invited to gauge the difference between the Friends and Job is through the different kinds of poetry they utter—the Friends stringing together beautifully polished clichés (sometimes virtually a parody of the poetry of Proverbs and Psalms), Job making constant disruptive departures in the images he uses, in the extraordinary muscularity of his language line after line.

The poetry Job speaks is an instrument forged to sound the uttermost depths of suffering, and so he adopts movements of intensification to focus in and in on his anguish. The intolerable point of culmination is not followed, as in Psalms, by a confident prayer for salvation, but by a death wish, whose only imagined relief is the extinction of life and mind, or by a kind of desperate shriek of outrage to the Lord.

When God finally answers Job out of the whirlwind, he responds with an order of poetry formally allied to Job’s own remarkable poetry, but larger in scope and greater in power (from the compositional viewpoint, it is the sort of risk only a writer of genius could take and get away with).

That is, God picks up many of Job’s key images, especially from the death-wish poem with which Job began (chap. 3), and his discourse is shaped by a powerful movement of intensification, coupled with an implicitly narrative sweep from the Creation to the play of natural forces to the teeming world of animal life. But whereas Job’s intensities are centripetal and necessarily egocentric,

God’s intensities carry us back and forth through the pulsating vital movements of the whole created world. The culmination of the poem God speaks is not a cry of self or a dream of self snuffed out but the terrible beauty of the Leviathan, on the uncanny borderline between zoology and mythology, where what is fierce and strange, beyond the ken and conquest of man, is the climactic manifestation of a splendidly providential creation which merely anthropomorphic notions cannot grasp.

Finally, this general predisposition to a poetic apprehension of urgent climactic process leads in the Prophets to what amounts to a radically new view of history. Without implying that we should reduce all thinking to principles of poetics, I would nevertheless suggest that there is a particular momentum in ancient Hebrew poetry that helps impel the poets toward rather special construals of their historical circumstances. If a Prophet wants to make vivid in verse a process of impending disaster, even, let us say, with the limited conscious aim of bringing his complacent and wayward audience to its sense, the intensifying logic of his medium may lead him to statements of an ultimate and cosmic character.

Thus Jeremiah, imagining the havoc an invading Babylonian army will wreak:

I see the earth, and, look, chaos and void,

the heavens—their light is gone.

I see the mountains, and, look, they quake,

and all the hills shudder (Jer. 4:23-24)

He goes on in the same vein, continuing to draw on the language of Genesis to evoke a dismaying world where creation itself has been reversed.

A similar process is at work in the various prophesies of consolation of Amos, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Isaiah: national restoration, in the development from literal to hyperbolic, from fact to fantastic elaboration, that is intrinsic to biblical poetry, is not just a return from exile or the reestablishment of political autonomy but—

- a blossoming of the desert,

- a straightening out of all that is crooked,

- a wonderful fusion of seed-time and reaping,

- a perfect peace in which calf and lion dwell together and a little child leads them.

Perhaps the Prophets might have begun to move in approximately this direction even if they had worked out their message in prose, but I think it is analytically demonstrable that the impetus of their poetic medium reinforced and in some ways directed the scope and extremity of their vision. The matrix, then, of both the apocalyptic imagination and the messianic vision of redemption may well be the distinctive structure of ancient Hebrew verse. This would be the most historically fateful illustration of a fundamental rule bearing on form and meaning in the Bible.

We need to read this poetry well because it is not merely a means of heightening or dramatizing the religious perceptions of the biblical writers—it is the dynamic shaping instrument through which those perceptions discovered their immanent truth.

Reviews

Reviews