[Please read the introduction to this post: Must Read: The Great Partnership: Science, Religion, and the Search for Meaning.

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks has his own website at http://www.rabbisacks.org.

Reformatted for this post is the whole Introduction that explains what to expect in every chapter; initially I intended to pick out only excerpts but while following the discussion, I just couldn’t stop typing the whole piece! Please notice as well that the Rabbi being British, uses British spelling of some English words, use of ‘s’ instead of ‘z’ for instance, or ‘ou’ for ‘u’.—Admin1.]

————————

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PART ONE God and the Search for Meaning

- The Meaning-Seeking Animal

- In Two Minds

- Diverging Paths

- Finding God

PART TWO Why It Matters

5. What We Stand to Lose

6. Human Dignity

7. The Politics of Freedom

8. Morality

9. Relationships

10. A Meaningful Life

PART THREE Faith and Its Challenges

11. Darwin

12. The Problem of Evil

13. When Religion Goes Wrong

14. Why God?

Epilogue: Letter to a Scientific Atheist

Notes

For Further Reading

Appendix: Jewish Sources on Creation, the Age of the Universe and Evolution

—————————

INTRODUCTION

If the new atheists are right, you would have to be sad, mad or bad to believe in God and practise a religious faith. We know that is not so. Religion has inspired individuals to moral greatness, consecrated their love and helped them to build communities where individuals are cherished and great works of loving kindness are performed. The Bible first taught the sanctity of life, the dignity of the individual, the imperative of peace and the moral limits of power.

To believe in God, faith and the importance of religious practice does not involve an abdication of the intellect, a silencing of critical faculties, or believing in six impossible things before breakfast. It does not involve reading Genesis 1 literally. It does not involve rejecting the findings of science. I come from a religious tradition where we make a blessing over great scientists regardless of their views on religion.

So what is going on?

Debates about religion and science have been happening periodically since the seventeenth century and they testify to some major crisis in society.

- In the seventeenth century it was the wars of religion that had devastated Europe.

- In the nineteenth century it was the industrial revolution, urbanisation and the impact of the new science, especially Darwin.

- In the 1960s, with the ‘death of God’ debate, it was the delayed impact of two world wars and a move to the liberalisation of morals.

When we come to a major crossroads in history it is only natural to ask who shall guide us as to which path to choose.

- Science speaks with expertise about the future, religion with the authority of the past.

- Science invokes the power of reason, religion the higher power of revelation.

The debate is usually inconclusive and both sides live to fight another day.

The current debate, though, has been waged with more than usual anger and vituperation, and the terms of the conflict have changed. In the past the danger — and it was a real danger –was a godless society. That led to four terrifying experiments in history—

- the French Revolution

- Nazi Germany

- the Soviet Union

- and Communist China.

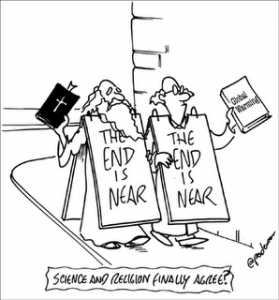

Today the danger is of a radical religiosity combined with an apocalyptic political agenda, able through terror and assymetric warfare to destabilise whole nations and regions. I fear that as much as I fear secular totalitarianisms. All religious moderates of all faiths would agree. This is one fight believers and non-believers should be fighting together.

Instead the new atheism has launched an unusually aggressive assault on religion, which is not good for religion, for science, for intellectual integrity or for the future of the West. When a society loses its religion it tends not to last very long thereafter. It discovers that having severed the ropes that moor its morality to something transcendent, all it has left is relativism, and relativism is incapable of defending anything, including itself. When a society loses its soul, it is about to lose its future.

So let us move on.

I want, in this book, to argue that we both need religion and science; that they are incompatible and more than incompatible. They are the two essential perspectives that allow us to see the universe in its three-dimensional depth. The creative tension between the two is what keeps us sane, grounded in physical reality without losing our spiritual sensibility. It keeps us human and humane.

The story I am about to tell is about the human mind and its ability to do two quite different things. One is the ability to break things down into their constituent parts and see how they mesh and interact. The other is the ability to join things together so that they form relationships. The best example of the first is science, of the second, religion.

Science takes things apart to see how they work.

Religion puts things together to see what they mean.

Without going into neuroscientific detail, the first is a predominantly left-brain activity, the second is associated with the right hemisphere.

Both are necessary, but they are very different. The left brain is good at sorting and analyzing things. The right brain is good at forming relationships with people. Whole civilisations made mistakes because they could not keep these two apart and applied to one the logic of the other.

When you treat things as if they were people, the result is myth: light is from the sun god, rain from the sky god, natural disasters from the clash of deities, and so on. Science was born when people stopped telling stories about nature and instead observed it; when, in short, they relinquished myth.

When you treat people as if they were things, the result is dehumanisation: people categorised by colour, class or creed and treated differently as a result. The religion of Abraham was born when people stopped seeing people as objects and began to see each individual as unique, sacrosanct, the image of God.

One of the most difficult tasks of any civilisation — of any individual life, for that matter — is to keep the two separate, but integrated and in balance. That is harder than it sounds. There have been ages — the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries especially — when religion tried to dominate science. The trial of Galileo is the most famous instance, but there were others. And there have been ages when science tried to dominate religion, like now. The new atheists are the most famous examples, but there are many others, people who think we can learn everything we need to know about meaning and relationships by brain scans, biochemistry, neuroscience and evolutionary psychology, because science is all we know or need to know.

Both are wrong in equal measure. Things are things and people are people. Realising the difference is sometimes harder than we think.

In the first part of the book I give an analysis I have not seen elsewhere about why it is that people have thought religion and science are incompatible. I argue that this has to do with a curious historical detail about the way religion entered the West. It did so in the form of Pauline Christianity, a religion that was a hybrid or synthesis of two radically different cultures, ancient Greece and ancient Israel.

The curious detail is that all the early Christian texts were written in Greek, whereas the religion of Christianity came from ancient Israel and its key concepts could not be translated into Greek. The result was a prolonged confusion, which still exists today, between the God of Aristotle and the God of Abraham. I explain in chapter 3 why this made and makes a difference, leading to endless confusion about what religion and faith actually are. In chapter 4 I tell the story of my own personal journey of faith.

In the second part of the book I explain why religion matters and what we stand to lose if we lose it. The reason I do so is that, I suspect, more than people have lost faith in God, they simply do not see why it is important. What difference does it make anymore? My argument is that it makes an immense difference, though not in ways that are obvious at first sight. The civilisation of the West is built on highly specific religious foundations, and if we lose them we will lose much that makes life gracious, free and humane.

We will, I believe, be unable to sustain the concept of human dignity. We will lose a certain kind of politics, the politics of common good. We will find ourselves unable to hold on to a shared morality — and morality must be shared if it is to do what it has always done and bind us together into communities of shared principle and value. Marriage, deconsecrated, will crumble and children will suffer. And we will find it impossible to confer meaning on human life as a whole. The best we will be able to do is to see our lives as a personal project, a private oasis in a desert of meaninglessness.

In a world in which God is believed to exist, the primary fact is relationship. There is God, there is me, and there is the relationship between us, for God is closer to me than I am to myself. In a world without God, the primary reality is ‘I’, the atomic self. There are other people, but they are not as real to me as I am to myself. Hence all the insoluble problems that philosophers have wrestled with unsuccessfully for two and a half thousand years. How do I know other minds exist? Why should I be moral? Why should I be concerned about the welfare of others to whom I am not related? Why should I limit the exercise of my freedom so that others can enjoy theirs? Without God, there is a danger that we will stay trapped within the prison of the self.

As a result, neo-Darwinian biologists and evolutionary psychologists have focused on the self, the ‘I’. ‘I’ is what passes my genes on to the next generation. ‘I’ is what engages in reciprocal altruism, the seemingly selfless behaviour that actually serves self-centered ends. The market is about the choosing ‘I’. The liberal democratic state is about the voting ‘I’. The economy is about the consuming ‘I’. But ‘I’, like Adam long ago, is lonely. ‘I’ is bad at relationships. In a world of ‘I’s, marriages do not last. Communities erode. Loyalty is devalued. Trust grows thin. God is ruled out completely. In a world of clamorous egos, there is no room for God.

So the presence or absence of God makes an immense difference in our lives. We cannot lose faith without losing much else besides, but this happens slowly, and by the time we discover the cost it is usually too late to put things back again.

In the third part of the book I confront the major challenges to faith. One is Darwin and neo-Darwinian biology, which seems to show that life evolved blindly without design. I will argue that this is true only if we use an unnecessary simplistic concept of design.

The second is the oldest and hardest of them all: the problem of unjust suffering, ‘when bad things happen to good people’. I will argue that only a religion of protest — of ‘sacred discontent’ — is adequate to the challenge. Atheism gives us no reason to think the world could be otherwise. Faith does, and thereby gives us the will and courage to transform the world.

The third charge made by the new atheists is, however, both true and of the utmost gravity. Religion has done harm as well as good. At various times in history people have hated in the name of the God of love, practised cruelty in the name of the God of compassion, waged war in the name of the God of peace and killed in the name of the God of life. this is a shattering fact and one about which nothing less than total honesty will do.

We need to understand why religion goes wrong. That is what I try to do in chapter 13. Sometimes it happens because monotheism lapses into dualism. Sometimes it is because religious people attempt to bring about the end of time in the midst of time. They engage in the politics of the apocalypse, which always results in tragedy, always self-inflicted and often against fellow members of the faith. Most often it happens because religion becomes what it should never become: the will to power. The religion of Abraham, which will be my subject in this book, is a protest against the will to power.

We need both religion and science. Albert Einstein said it most famously: ‘Science without religion is lame; religion without science is blind.’ It is my argument that religion and science are to human life what the right and left hemispheres are to the brain. They perform different functions and if one is damaged, or if the connections between them are broken, the result is dysfunction. The brain is highly plastic and in some cases there can be almost miraculous recovery. But no one would wish on anyone the need for such recovery.

- Science is about explanation. Religion is about meaning.

- Science analyses, religion integrates.

- Science breaks things down to their component parts. Religion binds people together in relationships of trust.

- Science tells us what is. Religion tells us what ought to be.

- Science describes. Religion beckons, summons, calls.

- Science sees objects. Religion speaks to us as subjects.

- Science practices detachment. Religion is the art of attachment, self to self, soul to soul.

- Science sees the underlying order of the physical world. Religion hears the music beneath the noise.

- Science is the conquest of ignorance. Religion is the redemption of solitude.

We need scientific explanation to understand nature. We need meaning to understand human behaviour and culture. Meaning is what humans seek because they are not simply part of nature. We are self-conscious. We have imaginations that allow us to envisage worlds that have never been, and to begin to create them. Like all else that lives, we have desires. Unlike anything else that lives, we can pass judgment on those desires and decide not to pursue them. We are free.

All of this, science finds hard to explain. It can track mental activity from outside. It can tell us which bits of the brain are activated when we do this or that. What it cannot do is track it on the inside. For that we use empathy. Sometimes we use poetry and song, and rituals that bind us together, and stories that gather us into a set of shared meanings. All of this is part of religion, the space where self meets other and we relate as persons in a world of persons, free agents in a world of freedom. That is where we meet God, the Personhood of personhood, who stands to the natural universe as we, free agents, stand to our bodies. God is the soul of being in whose freedom we discover freedom, in whose love we discover love, and in whose forgiveness we learn to forgive.

I am a Jew, but this book is not about Judaism. It is about the monotheism that undergirds all three Abrahamic faiths: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. It usually appears wearing the clothes of one of these faiths. But I have tried to present it as it is in itself, because otherwise we will lose sight of the principle in the details of this faith or that. Jews, Christians and Muslims all believe more than what is set out here, but all three rest on the foundation of faith in a personal God who created the universe in love and who endowed each of us, regardless of class, colour, culture or creed, with the charisma and dignity of his image.

The fate of this faith has been, by any standards, remarkable. Abraham performed no miracles, commanded no armies, ruled no kingdom, gathered no mass of disciples and made no spectacular prophecies. Yet there can be no serious doubt that he is the most influential person who ever lived, counted today, as he is, as the spiritual grandfather of more than half of the six billion people on the face of the planet.

His immediate descendants, the children of Israel, known today as Jews, are a tiny people numbering less than a fifth of a percent of the population of the world. Yet they outlived the Egyptians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Greeks and Romans, the medieval empires of Christianity and Islam, and the regimes of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, all of which opposed Jews, Judaism or both, and all of which seemed impregnable in their day. They disappeared. The Jewish people live.

It is no less remarkable that the small persecuted sect known as Christians, who also saw themselves as children of Abraham, would one day become the largest movement of any kind in the history of the world, still growing today two centuries after almost every self-respecting European intellectual predicted their faith’s imminent demise.

As for Islam, it spread faster and wider than any religious movement in the lifetime of its founder, and endowed the world with imperishable masterpieces of philosophy and poetry, architecture and art, as well as a faith seemingly immune to secularisation or decay.

All other civilisations rise and fall. The faith of Abraham survives.

If neo-Darwinism is true and reproductive success a measure of inclusive fitness, then every neo-Darwinian should abandon atheism immediately and become a religious believer, because no genes have spread more widely than those of Abraham, and no memes more extensively than that of monotheism. But then, as Emerson said, consistency is the hobgoblin of small minds.

What made Abrahamic monotheism unique is that it endowed life with meaning. That is a point rarely and barely understood, but it is the quintessential argument of this book. We make a great mistake if we think of monotheism as a linear development from polytheism, as if people first worshipped many gods, then reduced them to one. Monotheism is something else entirely. The meaning of a system lies outside of the system. Therefore the meaning of the universe lies outside the universe. Monotheism, by discovering the transendental God, the God who stands outside the universe and creates it, made it possible for the first time to believe that life has meaning, not just a mythic or scientific explanation.

Monotheism, by giving life a meaning, redeemed it from tragedy. The Greeks understood tragedy better than any other civilisation before or since. Ancient Israel, though it suffered much, had no sense of tragedy. It did not even have a word for it. Monotheism is the principled defeat of tragedy in the name of hope. A world without religious faith is a world without sustainable grounds for hope. It may have optimism, but that is something else, and something shallower altogether.

A note about the theological position I adopt in this book: Judaism is a conversation scored for many voices. It is, in fact, a sustained ‘argument for the sake of heaven’. There are many different Jewish views on the subjects I touch on in the pages that follow. My own views have long been influenced by the Jewish philosophical tradition of the Middle Ages — such figures as Saadia Gaon, Judah Hallevi and Moses Maimonides — as well as modern successors: Rabbis Samson Raphael Hirsch, Abraham Kook and Joseph Soloveitchik. My own teaher, Rabbi Nachum Rabinovitch, and an earlier Chief Rabbi, J.H. Hertz have also been decisive influences. Common to all of them is an openness to science, a commitment to engagement with the wider culture of the age, and a belief that faith is enhanced, not compromised, by a willingness honestly to confront the intellectual challenges of the age. For those interested in Jewish teachings on some of the issues touched on in this book, I have added an appendix of Judaic sources on science, creation, evolution and the age of the universe.

A note about style: often in this book I will be drawing sharp contrasts, between science and religion, left-and-right brain activity, ancient Greece and ancient Israel, hope cultures and tragic cultures, and so on. These are a philsopher’s stock-in-trade. It is a way of clarifying alternatives by emphasising extreme opposites, ‘ideal types’. We all know reality is never that simple. To give one example I will not be using, anthropologists distinguish between shame cultures and guilt cultures. Now, doubtless we have sometimes felt guilt and sometimes shame. They are different, but there is no reason why they cannot coexist. But the distinction remains helpful. There really is a difference between the two types of society and how they think about wrongdoing.

So it is, for example, with tragedy and hope. Most of us recognise tragedy, and most of us have experienced hope. But a culture that sees the universe as blind and indifferent to humanity generates a literature of tragedy, and a culture that believes in a God of love, forgiveness and redemption produces a literature of hope. There are no Sophocles in ancient Israel. There was no Isaiah in ancient Greece.

Throughout the book, it may sometimes sound as if I am setting up an either/or contrast. In actuality I embrace both sides of the dichotomies I mention: science and religion, philosophy and prophecy, Athens and Jerusalem, left brain and right brain. This too is part of Abrahamic spirituality. People have often noticed, yet it remains a very odd fact, indeed, that there is not one account of creation at the beginning of Genesis, but two, side by side, one from the point of view of the cosmos, the other from a human perspective. Literary critics, tone deaf to the music of the Bible, explain this as the joining of two separate documents. They fail to understand that the Bible does not operate on the principles of Aristotelian logic with its either/or, true-or-false dichotomies. It sees the capacity to grasp multiple perspectives as essential to understanding the human condition. So always, in the chapters that follow, read not either/or but both/and.

* * * * * * * *

The final chapter of this book sets out my personal credo, my answer to the question, ‘Why believe?’ It was prompted by the advertisement, paid for by the British Humanist Association, that for a while in 2009 decorated the sides of London buses: ‘There’s probably no God. Now stop worrying and enjoy your life.’ I hope the British Humanists will not take it amiss if I confess that this is not the most profound utterance yet devised by the wit of man. It reminds me of the remark I once heard from an Oxford don about one of his colleagues: ‘On the surface, he’s profound; but deep down, he’s superficial.’ Of course you cannot prove the existence of God. This entire book is an attempt to show why the attempt to do so is misconceived, the result of an accident in the cultural history of the West. But to take probability as a guide to truth, and ‘stop worrying’ as a route to happiness, is to dumb down beyond the point of acceptability two of the most serious questions ever framed by reflective minds. So, if you want to know why it makes sense to believe in God, turn to chapter 14.

Atheism deserves better than the new atheists, whose methodology consists in criticising religion without understanding it, quoting texts without contexts, taking exceptions as the rule, confusing folk belief with reflective theology, abusing, mocking, ridiculing, caricaturing and demonising religious faith and holding it responsible for the great crimes against humanity. Religion has done harm; I acknowledge that candidly in chapter 13. But the cure of bad religion is good religion, not no religion, just as the cure of bad science is good science, not the abandonment of science.

The new atheists do no one a service by their intellectual inability to understand why it should be that some people lift their eyes beyond the visible horizon or strive to articulate an inexpressible sense of wonder; why some search for meaning despite the eternal silences of infinite space and the apparent random injustices of history; why some stake their lives on the belief that the ultimate reality at the heart of the universe is not blind to our existence, deaf to our prayers, and indifferent to our fate; why some find trust and security and strength in the sensed, invisible presence of a vast and indefinable love. A great Jewish mystic, the Baal Shem Tov, compared such atheists to a deaf man who for the first time comes on a violinist playing in the town square while the townspeople, moved by the lilt and rhythm of his playing, dance in joy. Unable to hear the music, he concludes that they are all mad.

Perhaps I am critical of the new atheists because I had the privilege of knowing and learning from deeper minds than these, and I end this introduction with two personal stories to show that there can be another way. I had no initial intention of becoming a rabbi, or indeed of pursuing religious studies at all (I explain what changed my mind in chapter 4). I went to university to study philosophy. My doctoral supervisor, the late Sir Bernard Williams, described by The Times in his obituary as ‘the most brilliant and most important British moral philosopher of his time’, was also a convinced atheist. But he never once ridiculed my faith; he was respectful of it. All he asked was that I be coherent and lucid.

He stated his own credo at the end of one of his finest works, Shame and Necessity:

We know that the world was not made for us, or we for the world, that our history tells no purposive story, and that there is no position outside the world or outside history from which we might hope to authenticate our activities.

Williams was a Nietzchean who believed that not only was there no religious truth, there was no metaphysical truth either. I shared his admiration for Nietzsche, though I drew the opposite conclusion — not that Nietzsche was right, but that he, more deeply than anyone else, framed the alternative: either faith or the will to power that leads ultimately to nihilism.

William’s was a bleak view of the human condition but a wholly tenable one. His own view of the meaning of a life he expressed at the end of that work in the form of one of Pindar’s Odes:

Take to heart what may be learned from Oedipus:

If someone with a sharp axe

Hacks off the boughs of a great oak tree,

And spoils its handsome shape;

Although its fruit has failed, yet it can give an account of itself

If it comes later to a winter fire,

Or if it rests on the pillars of some palace

And does a sad task among foreign walls,

When there is nothing left in the place it came from.

I understood that vision, yet in the end I could not share his belief that it is somehow more honest to despair than to trust, to see existence as an accident rather than as invested with meaning we strive to discover. Sir Bernard loved ancient Greece; I loved biblical Israel. Greece gave the world ltragedy; Israel taught it hope. A people, a person, who has faith is one who, even in the darkest night of the soul, can never ultimately lose hope.

The only time he ever challenged me about my faith was when he asked, ‘Don’t you believe there is an obligation to live within one’s time?’ It was a fascinating question, typical of his profundity. My honest answer was, ‘No.’ I agreed with T.S. Eliot, that living solely within one’s time is a form of provincialism. We must live, not in the past but with it and its wisdom. I think that in later years, Williams came to the same conclusion, because in Shame and Necessity, he wrote that ‘in important ways, we are, in our ethical situation, more like human beings in antiquity than any Western people have been in the meantime’. He too eventually turned for guidance to the past. Despite our differences I learned much from him, including the meaning of faith itself. I explain this in chapter 4.

The other great sceptic to whom I became close, towards the end of his life, was Sir Isaiah Berlin. I have told the story before, but it is worth repeating, that when we first met he said, ‘Chief Rabbi, whatever you do, don’t talk to me about religion. When it comes to God, I’m tone deaf!’ He added, ‘What I don’t understand about you is how, after studying philosophy at Cambridge and Oxford, you can still beleive!

‘If it helps,’ I replied, ‘think of me as a lapsed heretic.’

‘Quite understand, dear boy, quite understand.’

In November 1997, I phoned his home. I had recently published a book on political philosophy which gave a somewhat different account of the nature of a free society than he had done in his own writings. I wanted to know his opinion. He had asked me to send him the book, which I did, but I heard no more, which is why I was phoning him. His wife, Lady Aline, answered the phone and with surprise said, ‘Chief Rabbi — Isaiah has just been talking about you.’

‘In what context?’ I asked.

‘He’s just asked you to officiate at his funeral.’

I urged her not to let him think such dark thoughts, but clearly he knew. A few days later he died, and I officiated at the funeral.

His biographer Michael Ignatieff once asked me why Isaiah wanted a religious funeral, given that he was a secular Jew. I replied that he may not have been a believing Jew but he was a loyal Jew. In fact, I said, the Hebrew word emunah, usually translated as ‘faith’, probably means ‘loyalty’. I later came across a very significant remark of Isaiah’s that has a bearing on some of today’s atheists:

I am not religious, but I place a high value on the religious experience of believers . . . I think that those who do not understand what it is to be religious, do not understand what human beings live by. That is why dry atheists seem to me blind and deaf to some forms of profound human experience, perhaps the inner life: It is like being aesthetically blind.

Since then, I have continued to have cherished friendships and public conversations with notable sceptics like the novelists Amos Oz and Howard Jacobson, the philosopher Alain de Botton, and the Harvard neuroscientist Steven Pinker (my conversation with Pinker figures in the recent novel by his wife Rebecca Goldstein, entitled 36 Arguments for the Existence of God, subtitled A Work of Fiction).

The possibility of genuine dialogue between believers and sceptics show why the anger and vituperation of the new atheists really does not help. It does not even help the cause of atheism. People who are confident in their beliefs feel no need to pillory or caricature their opponents. We need a genuine, open, serious, respectful conversation between scientists and religious believers if we are to integrate their different but conjointly necessary perspectives. We need it the way an individual needs to integrate the two hemispheres of the brain. That is a major theme of the book.

When he last visited us, I asked Steven Pinker whether an atheist could use a prayer book. ‘Of course,’ he said, so I gave him a copy of one I had just newly translated. I did not pursue the subject further but I guess, if I had asked, that he would have told me the story of Niels Bohr, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist and inventor of complementarity theory.

A fellow scientist visited Bohr at his home and saw to his amazement that Bohr had fixed a horseshoe over the door for luck. ‘Surely, Niels, you don’t believe in that?’

‘Of course not,’ Bohr replied. ‘But you see –the thing is that it works whether you believe in it or not.’

Religion is not a horseshoe, and it is not about luck, but one thing many Jews know — and I think Isaiah Berlin was one of them — is that it works whether you believe in it or not. Love, trust, family, community, giving as integral to living, study as a sacred task, argument as a sacred duty, forgiveness, atonement, gratitude, prayer: these things work whether you believe in them or not. The Jewish way is first to live God, then to ask questions about him.

Faith begins with the search for meaning, because it is the discovery of meaning that creates human freedom and dignity. Finding God’s freedom, we discover our own.